|

Home

FAQ

The Book

Articles

Links

Contact

|

|

Saving Star Wars: The Special Edition Restoration Process and

its Changing Physicality

Many are aware that Star

Wars was restored for its 1997 theatrical re-release, as video

featurettes and television specials from the time often touted that

the original negative was in poor condition and couldn't be shown as

was. Somehow, as if by magic, the film ended up playing in theatres

in January 1997 looking like it had when it was first shown twenty

years earlier, arguably looking better than it had when it was first

shown twenty years earlier. Featurette's talk about "washing the

film" and "digitally re-compositing" the bluescreen elements, but

these blur the line between restoration and enhancement, for the

digital processing and elements added are outside of the

restoration process itself. Fans and even many experts don't

seem to have been able to trace exactly what was enacted to preserve

the film; there are a couple articles and factoids floating around

the internet and in books, but there's never been an exhaustive

synthesis of all of this data, for it lurks in piecemeal form (the

best sources are ILM: Into the Digital Realm, and the

February 1997 issue of American Cinematographer). I am

hoping that this article will amend this, and also inform people on

the history of Star Wars as a physical medium, as the way

in which we view and engage with it.

The restoration of Star

Wars was a complicated and costly endeavor. Firstly, it should

be noted, is the great irony that the restoration of Star

Wars was used only as a means to revise the film, in effect,

not only not restoring it, but making great changes that

had no part in the original. The prevalent motivation for changes as

somehow constituting a rectification of things that were always

"meant to be", that the digital alterations are bringing the film

closer to the way "it was intended to be" and hence constituting a

metaphoric restoration of sorts, further obscures this fact. While

some changes were enacted to re-introduce portions originally (and

intentionally) left out of the film--like the Jabba scene,

which was never intended to feature an alien Jabba anyway--the bulk

of them were enacted for pure revisionism, as Lucas and the effects

wizards admitted at the time (though not so much today). It was

"an experiment in learning new technology," as Lucas said

at the time, [1] research for ILM that Fox

was paying for, and most new shots and altered shots were the

product of ILMers Tom Kennedy and Denis Muren, and art director

TyRuben Ellingson, rather than Lucas. [2]

I will not dwell on this point

other than highlighting the fact that advertised "restorations"

are not always the same as preservations, and while preservation of

the film as it was is ideally and normally the goal of a

restoration, such is not the case for Star Wars, whose

final product is not a "restored version" but an enhanced version

that uses restored elements. Lawrence of Arabia, for

example, is often touted as having been restored in 1991, but in

fact many scenes were not part of any version seen until then--the

difference here is that these scenes were meant to be included

in the original release of Lawrence of Arabia, hence it is

restoring footage originally forced out in addition to repairing the

physical negative to its original state; Star Wars'

released "restoration," on the other hand, does not contain any

items originally cut out or originally intended for inclusion--only

two new bits are from the original shoot: the Jabba scene which has

a central digital special effect never part of the original scene

(and, as far

as I can tell, was never intended to be, despite what Lucas

says), and a short moment between Luke and Biggs (even here there is

a new special effect--a digital foreground character wipes by to

hide a cut to the scene where Luke's non-Darth-Vader father is

discussed). Both of these were excised by Lucas deliberately, as he

had final cut in 1977. There is some debate about whether David Lean

is engaging in revisionism himself, but, even if he is, the scenes

included constitute an acceptable director's cut that would have

been possible when the film was made, rather than Lucas' case, where

he admits he is being fanciful. I will say no more on this other

than motion picture marketing has long used the term restoration as

a conflation for revision, and in the case of Star Wars

there has been more revision than any other

example.

Although this article will explain

about how the Special Edition(s) were created, this is not to be the

focus of the article--instead we will look mainly at the physical,

and non-physical, process by which the original negative of the film

was created and repaired. This is normally the point of a

restoration, and though I just a moment ago spoke of this not being

the case for Star Wars, the other great irony is that it,

at one point, was--before Lucas and ILM could enact the enhancement

and alteration of the original content, the film was restored to its

original state, the original negative meticulously and painstakingly

repaired. This restoration was then used as the basis for digital

additions, in effect making the restoration lost.

Background

The path to the restoration and the

Special Edition begins in 1993. [3] With a

renaissance of Star Wars merchandising and general

interest, Fox and Lucasfilm representatives met to discuss how to

celebrate the 20th anniversary in four years time. [4] An elaborate convention had been had in 1987 to

celebrate the film's first decade, and this was suggested as a

viable option for 1997 as well. Lucas, however, had just adopted his

third child and first son, who was still an infant; as he had yet to

show him the Star Wars movies on video, Lucas felt that a theatrical

re-release would give him, and everyone else, the experience that

the film was meant to be viewed under, on a massive scale outside

the home and with hundreds of other people. [5]

Fox evidently was enthusiastic about the idea, and when Lucas

realised how much work this would entail, he felt that he could deal

with a sore point that had always bothered him about the film: the

Mos Eisley sequence. His main concern was that the spaceport was not

capable of being portrayed of as a bustling hub of activity the way

he wanted, and he had a deleted scene of Jabba the Hutt as

well. [6] The last point was especially

interesting--since Lucas brought the character back in a very

prominent role in Return of the Jedi, his scene in the

original film was relevant again. This might have occurred to him as

far back as that third film--sketches exist showing how an early

version of Jabba could have been matted into the existing footage,

probably with the 1981 re-release in mind (that release also had a

brand new title crawl to further link the films). [7]

"The initial scope of it involved

two dozen shots," ILMer Tom Kennedy says. [8]

Denis Muren at ILM also drew up a list of shots that had always

bothered him, mainly in spaceship motion, which Lucas was open to

using, and Tom Kennedy and others then contributed ideas for new

additions [9] --since Fox was paying for it all,

it was looked at as free R&D for ILM to use for the prequels

Lucas was also planning. [10]

Rick McCallum was serving as

producer for the re-release, which was now becoming more and

more elaborate. It soon became apparent how elaborate it would be.

Existing Interpositive prints (IPs) and Internegatives (INs) were

not ideal to make new prints from for the re-release, since they

were aging and partly damaged from use. It would make sense to go to

the highest quality source as a base anyway--the original negative

(O-neg).

A word about this may be necessary

for the non-technical. The original negative is the master celluloid

from which all other copies are made from. It is made out of the

original pieces of film which went through the camera itself on the

set. This makes it very precious--any damage done to the negative

means that the damage will be permanent and undoable, so it is

handled as little as possible, and under carefully controlled lab

conditions. From this raw footage, a copy is made for the editor to

work with, so that the original camera negatives are not handled.

The editor then makes his edit using this copy (the workprint). When

he or she is done, the workprint is passed on to the lab. The

editor's copy is made out of different shots put together (with

tape, literally), and now this must be replicated precisely using

the high-quality originals. This is accomplished by use of

edge-coding--each frame of film has a code printed on it that the

laboratory can reference. A person called a negative cutter then

takes the original negatives--the original camera negatives--and

carefully cuts portions out that correspond to the cuts on the

workprint; by using the edge-coding, he or she can make sure that

this replica is made of exactly the same shots and frames as the

editor has indicated. These portions of the camera negatives are

then glued together into an edit of the film that matches the

editor's. Any mistake here can be disastrous, as the process of

glueing the pieces of film together destroys the next frame, which

makes it irretrievably lost since these are the originals. When

done, we have what is called the original negative, which is the

original camera pieces conformed to an edit of the

film.

The process of bringing this to

theatres is even more complicated though. In order to avoid handling

the original negative, a copy is made. This is called an

Interpositive (IP), and is the second-highest-quality source of the

film. Copying this will give us another negative image,

however, so it cannot be used to make theatrical prints (the colors

will be reversed). So it is copied, resulting in an Internegative

(IN), which theatrical prints can then be made from (copies of a

copy of a copy of the original negative). Star Wars was a

popular film, and over the years so many theatrical prints were made

that the IPs/INs got worn out, and new ones had to be made. The last

one made was in 1985, intended to be a master copy for home video

releases. [11] Because each copy degrades the

image, when the anniversary re-release came up the original negative

naturally was sought as the highest quality source to make a new

version from.

Lucas had screened some prints in

1994 but none of them were presentable. "By the summer of '94

George said, 'I'm worried about the negative because every print we

get is bad,'" Rick McCallum remembers. "That's when we got really

scared about the presentation of this film." [12]

What they found when they opened up

the cans of film in late 1994 [13] was

horrifying--the original negatives had been severely deteriorated.

Because film is photo-chemical it is prone to aging and the colors

will fade like a newspaper; usually the yellow layer goes first,

resulting in blue-tinted images and purple skin tones. This is what

happened with Star Wars, where much of the film's existing

prints had also faded to red. This aging process is expected,

but the film was less than twenty years old and had looked fine

less than a decade earlier when the last IP was made--the film

should not have been as deteriorated as it was. In some places the

image was so degraded that it was unusable, plus there was the

normal wear from handling damage and shrinking/swelling that occurs

in the celluloid aging process.

Lab technicians began wondering how

it was that the film could have deteriorated so much. Fox stored its

negatives far away from Earthquake-prone L.A., hundreds of feet

underground in Kansas, at optimal temperatures of 50-53 degrees.

[14] As it turns out, the disease was not unique

to Star Wars--films from the same era had the same

affliction. The reason was because of the chemical composition of

the film stock in use at the time. Prior to 1983, all negative film

stocks were what archivists now call "quick fade"; Kodak was among

the worst, and their negatives had to be corrected every five years

to compensate for fading (often the cyan went first), and their

release prints even poorer, beginning to fade to red after only five

or six years. Due to pressure from filmmakers and experts (among

them, Martin Scorsese), companies started developing more stable

stocks in the early 80s, and by 1982 Kodak had developed its

"low-fade" negative and print stocks. As a result, color negative

films from 1952-1982 are in states of serious disrepair. Star

Wars faced additional challenges in that one of its

negative stocks, Color Reversal Intermediate (CRI) 5249, was so

prone to fading that Kodak stopped making it in 1987--but 62 shots

in Star Wars were on the stock, none of them usable. [15] Being an intermediate stock, used for making

dupes directly from the negative, this was probably what many

optical composites were printed on, including the many wipes,

dissolves and transitions; this was not commonly used for feature

films (usually television), and may have been a cost-saving measure.

"If George had wanted to do something even more creative to an

optical shot, like flop it or add an overriding zoom, and there

wasn't a lot of time, they used CRI as an intermediate reversal

stock to alter those few effects shots after the fact," Tom Kennedy

reported. [16]

Ted Gagliano remembers, "When I had

first seen the print at DeLuxe, I was shocked. I was a Marin

[County] high school student when I first saw Star Wars and

it had been so spectacular--it was the reason I ultimately went into

the movie business. But after seeing the dirt and the problem of

fading it didn't have the same feeling. It looked like an old movie.

At the ILM screening I had prepared everybody for what they were

going to see, and afterward Lucas said to me: 'Well, the speech was

worse than the viewing.' I think he was disappointed but slightly

relieved. He could tell it was fixable. The challenge was to

integrate the new [special edition] footage into a good negative."

[17]

Leon Briggs, a former veteran of

Disney Lab who was brought in to restore Star Wars, says

that 10-15% of the original color had faded, [18] but judging by some of the examples shown it was

at least double that in some cases. In addition, the negative was

discovered to have been in a state of disrepair for other

reasons--the popularity of the film meant that the negative was

handled and printed many times over the previous two decades, and it

was marked with dirt and scratches, more than is normal, with some

theatrical prints struck directly from it; with the last wide

theatrical showing in 1981 the negative had been okay back then, but

by the mid-90s the damage that was acceptable in subsequent home

video versions would not hold up when projected on a theatrical

screen. "They made far too many release prints off the original

neg," Kennedy says. "After 20th Century Fox reprinted Star

Wars from the negative, we saw all the various levels of

quality we could get out of the original cut, and we discovered some

interesting and frightening things." [19]

The Restoration Begins

The restoration of Star

Wars began in 1995 and took the combined efforts of three

companies, [20] under the payroll of Twentieth

Century Fox: Pacific Titles, who handled optical printing,

Lucasfilm, who organized the restoration and brought in ILM, and YCM

Labs, who were responsible for color timing (arguably the most

important of the three, since the faded colors were the biggest

concern), as well as the supervision of film restoration consultant

Leon Briggs and Fox's head of post-production Ted Gagliano. To

start, Briggs had the negative cleaned, removing dirt and grime that

had accumulated in its many years of use, by running it through a

104-degree sulfur bath solution and then hand-wiping it [21]. Star Wars' negative

contained four separate types of film stocks [22] (Kodak 5243, an intermediate, probably for

composites, 5247, a fine grain 100 EI tungsten stock that the

live action must have been shot on, and 5253, an intermediate

used as a separation stock that all visual effects elements

were shot on [see note], plus the CRI stock

[23]), however, and two of them could not be subjected to the

solution and needed to be addressed on their own [24]. Each stock had to be washed separately anyway,

unlike conventional restoration where the negative would have been

washed in one piece and then wiped by hand [25],

and so the negative was carefully disassembled.

"That made everybody suck in their

breath," recalls Tom Kennedy, effects producer on the release.

"Thankfully, Robert Hart, the neg cutter on the second and third

films, came in to put the negative back together."

[26] When this process was over, much of

the dirt that had plagued previous releases (which, when projected,

is often mistaken for grain) was gone and a clear image was had.

It would have been far too cost

prohibitive to scan and digitally restore the entire film at that

time, so only the shots that were going to be enhanced with digital

effects ended up in the computer. "After selectively cleansing the

negative they'd remove and send us those piece sections of the

original negative for which we were doing the special edition work,"

reports Tom Kennedy. [27] This was to the

viewer's benefit--though perhaps better than optical compositing,

scanning technology back then was only as advanced as 2K resolution,

not much more than standard HD (which also means all the SE

enhancements are at this res), so it was better that only portions

ended up in this downgrade. "After doing various tests, we found out

right away that nothing beats scanning original negative. Star

Wars was an A-B neg cut, which meant that they could actually

lift and slug original negative and send it back to ILM whenever we

were enhancing a live-action shot. I think this is the first time

someone has tried to bring a Seventies effects film back to the big

screen." [28] For parts of the negative that

were damaged, ILM preferred to use a scan from an IP instead, says

Kennedy in ILM: Into the Digital Realm. [29]

While ILM worked on digital

upgrades, the degrading CRI shots needed to be addressed. Because

some were made from different composites on an optical printer, even

in the best of conditions there would be heavy dupe grain and extra

dirt that was printed on the image itself and couldn't be removed.

One can see this in the scene where Luke activates the lightsaber in

Ben's hovel--the moment the special effect enters the shot, the

level of dirt and grain jumps noticeably (this was also shot on

normal 35mm cameras, rather than the higher quality Vistavision,

because the saber effects were originally to be in-camera). What was

worse was that this didn't just plague special effects shots but

shots with wipes or dissolves, and the generation loss was there

whether they were printed on CRI or regular Kodak Eastman stock. The

solution, then, was to go back to the original pieces and make new

composites. For instance, in a scene with a wipe transition, the

original two shots blended with the wipe were still in storage

somewhere, with the O-neg piece being a second-generation duplicate

of them combined together.

Ironically,

just as ILM was retiring optical printers and moving into the

digital realm, the technology was resurrected again. Pacific Titles

had eleven state of the art, modern optical printers with new

lenses, which, when combined with Kodak's finest film stock, gave "a

boost in resolution and color saturation," according to company

vice-president Phillip Feiner. [30] They

re-composited all wipes and transitions (the "bread and butter"

opticals, as Feiner calls them). These new negatives were then cut

into the O-neg, replacing the originals (which, I must presume, were

put in storage). One caveat of this is that each time the negative

has a new portion of film cut into it, a frame on either side of it

is lost in the process of cementing the new film piece into the

reel; if one compares closely the SE to the previous releases, one

finds that any new shot is missing a few frames at the head and

tail, though the difference is imperceptible when in

motion.

The

visual effects shots were faced with the same problems as the

conventional opticals: a deteriorated film stock (in CRI instances;

in others, milder color fading), and dupe grain and dirt. The shots

also contained matte lines, which were beginning to become a thing

of the past as films began to utilize digital compositing. Footage

from documentaries on the SE reveals that ILM had gone back to the

original special effects elements, which had been meticulously

saved, and then scanned and digitally recomposited them (in

some instances, their placement is slightly different than the

original, even though the principle was to match them as closely as

possible--for instance, the seeker ball in the scene of Luke's

Millennium Falcon training is positioned not quite the same as the

original composite, though the difference is basically imperceptible

while in motion). In American Cinematographer, it is never

stated that this re-compositing process was enacted for every

visual effect, but it seems that at the very least most of them

were. [31] When these were finished, they

were printed back onto film and cut into the O-neg, again replacing

the originals. The O-neg was slowly being subsumed by new

material.

But meanwhile, the rest of the film

needed to be tackled. Most of the negative could be addressed by

simply color-timing the image to get rid of the blue and pink shift

that had occurred, but some parts were in more serious need of

repair. What the policy was here is unclear--were the portions that

were ripped and damaged, or normal live-action printed on CRI (i.e.

if it had been flipped optically), replaced with new negatives

culled from IPs? There have been unofficial sources that have

suggested as much, and this was certainly the case with the ILM

scans, but it's not always clear if the O-neg itself gained new

physical pieces made from second-generation prints.

ILM: Into the Digital

Realm states that the IP was used to restore the

negative, but later it is said that this was done on

occassion by ILM for their work (i.e. re-compositing effects, adding

CG). ILM: Into the Digital Realm does, however, imply

that there was new negative pieces made from the original separation

masters. Separation masters are black and white prints (on

color film, that is) of each color spectrum of the

negative--yellow, cyan and magenta. Each of these color fields are

preserved on special metallic silver compositions, which never fade,

and which, when re-combined, give a perfect re-construction of the

original negative. Ted Gagliano states: "You know the original

negative will fade, so you can turn to the separation masters; it's

the record of what it'll look like and it'll last forever. So the

negative you make off your YCMs should be just as good as the

original negative." [32] The negative was being

cannibalized by other pieces.

Much of the "corrected" version of

the O-neg was accomplished by the work of YCM Labs, who combated the

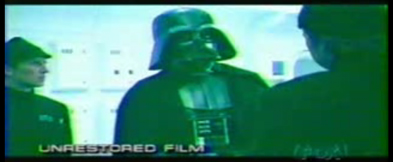

color fading by re-timing the image to bring back its lustre. "Darth

Vader isn't black anymore," says Pete Comandini, engineer at the

company, "he starts out coming up to a navy blue and then getting

brighter and brighter as the film continues to deteriorate." [33] To guide them in how the film should look, they

used dye-transfer Technicolor prints. Technicolor was still making

dye-transfer prints in the late 70s in the United Kingdom, though

they would soon phase them out. Rather than using chemicals to make

release prints, like Kodak or DeLuxe, which had bad contrast, poor

color reproduction and heavy grain, but are inexpensive and easy to

make, these prints were made of three strips of dyed film, which

gave the prints a vibrant image with a very fine grain structure.

More importantly, because they are not chemical but dye-based, they

never fade. George Lucas loaned YCM Labs his very own personal

Technicolor print, which still looked the same as it had when he put

it in storage some twenty years earlier. "George had a private

[Technicolor] print in the basement of his home," Gagliano notes.

"For the color timing he told us to go for that look: 'That's the

Star Wars I made,' he told us." [34]

(from

Star Wars, The Magic and Mystery--the shots may be slightly

more green-shifted, rather than blue-shifted, due to

capture)

Since much of the restoration was

color-timing accomplished by YCM Labs, this begs the

conclusion--since the negs themselves can't be physically altered,

the restoration's final product must have been a new IP with correct

coloring. Whenever films are color-timed, it is the Interpositives

from which theatrical prints work from--original negatives do not

contain any color-timing information, so whenever a release goes

back to the original negatives, all the color-timing is lost and the

film must be re-timed from scratch all over again. It is doubtful

that an entirely new negative was struck from the corrected IP for

Star Wars, which might explain why Lucas enacted a second

color-timing effort in 2004 when he returned to the original

negatives.

Had the film remained like this, we

would have a restored version of Star Wars, perfectly

matching the original release but with pristine quality, even to the

point where it was better than what could have been possible back

then (as with the higher quality optical transitions). However, this

was only part of the process of making what was eventually called

"The Special Edition." ILM was working on many dozens of new shots,

and an even larger amount of enhanced shots, using digital effects

to re-do, expand, re-edit and otherwise alter many scenes in

the film. When these were completed, they apparently

were printed onto film and re-cut into the negative, replacing

the original negs, which were undoubtedly put back into

storage. As a result, the negative for Star Wars is

filled with CGI-laden modern alterations. When Lucas says that the

original version physically does not exist, this is what he really

means--the negative is conformed to the Special Edition. Of course,

it would be very easy to simply put the original pieces back and

conform it to the original version, or use the separation masters

and IPs, or simply scan the old pieces for a digital

restoration, but I digress.

The Special Edition of Star

Wars was frequently reported in the media as costing as much as

$20 million to enhance and restore, though some sources claimed as

low as $10 million. [35] In any case, the

film's restoration and enhancement cost more than the original

production itself--all of it being paid for by Twentieth Century

Fox. At the time, spending upwards of $20 million on a decades-old

film that, back then, was only to be a limited release, was a very

big gamble. Many speculated that they did so in order to win

Lucas' favor and get a chance at distributing the Star

Wars prequels that went to camera a few months later. As

the Special Edition drew greater and greater interest, it

was decided to do a full-scale release, rather than a limited one.

On January 31st, 1997, the Special Edition of Star Wars

opened in theatres. The film became the biggest January opener in

history, and earned $138 million, making the twenty-year-old film

one of the top money makers of that year. It was released on VHS and

Laserdisk in August--unfortunately, in the telecine the film

received a pink tint, making the color referencing and restoration

that YCM Labs did lost (you can tell this pink tint is from the

telecine and not the negatives because it's on the CG shots as

well). It was released again in 2000--this time removing the titling

of "Special Edition." Because this was supposed to supplant the

original, all prints in circulation of the original were recalled

(studios control all rented prints--none are sold privately, though

a black market exists), and possibly destroyed (studio print masters

are, of course, kept). Today, Fox/Lucasfilm--Lucasfilm gained the

rights in 1998 or 1999--only loans out prints of the Special Edition

(no theatrical prints were ever made of the 2004

SE).

Further Changes

and into the Digital Realm

The changing state of Star

Wars didn't end there, of course. In 2004, a second round of

alterations was released for the DVD debut of the trilogy. The

process of creating this was markedly different from the Special

Edition of 1997, however. Perhaps reflecting the computer advances

that had been made since, this version was created entirely in the

digital realm.

The film needed to be digitized to

release it on DVD in the first place, and when Lucas decided to make

further changes to the film, the highest quality source was sought

for scanning--the negatives. This would create a new master digital

negative that would serve as a base for Lucas' definitive version of

the film. There are a number of caveats that resulted from this,

however.

One was that the negative was

scanned only in HD resolution of 1080p, in 10-bit

RGB. [36] This was a state worse than the

primitive 2K scans ILM had done for the SE. By contrast, when

Blade Runner was restored and enhanced in 2007, the

live-action was scanned at 4K, the normal standard, and the visual

effect shots at 8K. Godfather's 2008 restoration was

scanned at 4K for the entire film, while Wizard of Oz's

2009 release was done at 8K. Why Lucas chose to source his master

from a paltry 1080 HD scan is hard to fathom, especially when 4K was

long in place as the standard, with 6K and 8K looming on the horizon

as a viable replacement since data storage was becoming cheaper. One

reason may be because Lucas was shooting the two

prequels--Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the

Sith--on the Sony CineAlta, which itself was 1080 (being the

first generation of HD feature-film cameras). This is another

undoable element of the prequels--filmed on 1080p HD, they have, at

the most, less than half the resolution of the 35mm original

trilogy, with some arguing that 35mm resolves 5000 lines, meaning

they have just under 1/5 the resolution (Phantom

Menace was shot in 35mm, but then scanned in 2K--which is still

an improvement over the following two films). With the new 2004 SE

existing partly to link the six films, this was indeed the case as

the original trilogy was lowered in resolution to that of the first

three episodes. Ironically, as Lucas moved into more "high tech"

digital arenas, the quality of the image slowly declined, going

from a 35mm original, to a partly-2K 1997 SE and then a fully-1080p

2004 SE. According to Videography, the negs were scanned on

a Cintel C-Reality telecine, at 1920x1080 resolution, in 4:4:4 RGB,

recorded to Sony SR tape. [37]

The second caveat that resulted

from scanning the O-neg is one that was irrespective of the output

resolution, and this was that they were once again working from a

copy of the film without color-correction, since the meticulous work

YCM Labs did existed only on the SE's Interpositive (again, the

O-neg can't have its physical image corrected, it has to be produced

on a copy). Perhaps because of the fact that Lucas had lost all of

his color-work, he embarked on a new principle--instead of

faithfully reproducing the look of the original release and

photography, as had been the case on the previous re-release, it

could be digitally manipulated to have a slicker look that matched

the high-saturation, high-contrast look of the three

prequels.

The 2004 SE (it has never been

marketed as a Special Edition, though there really is no other label

to describe it) had its color correction guided and supervised by

George Lucas himself. [38] Screening the film at

Skywalker Ranch, Lucas went through the film with members from ILM,

who would be color-timing the digitized film themselves at

Lucas' approval. [39]

This is one of the most

controversial aspects of the release. While the revised film

obviously is meant to have a deliberate look, what was released is a

sloppy mess, in technical terms; blacks are crushed, colors bleed

and pop distractingly, video noise is visible because of the

oversaturation, skin tones are inconsistent and often very pink,

scenes have weird casts to them (i.e. the Millennium Falcon scenes

look very green), everything is much too dull and dim, contrast is

not nominal, and many of the lightsaber effects are the wrong color

(pink for Vader, green for Luke). The coloring is not even

consistent with the prequels in some instances, whereas the

originals were--for instance, the original blockade runner scene was

meant to be Kubrick-esque bright white, while on the 2004

release it is a dull blue, yet strangely in Revenge of the

Sith it is the bright white it is supposed to be. Lowry is

often mistakenly pointed at as the culprits of these highly

noticeable flaws, but in fact it is Lucas himself. The final DVD

product has been screened for Lucas multiple times since, such as at

Celebration III.

Videography magazine

describes the re-coloring of the original film as done by

postproduction engineer Rick Dean [40];

Empire and Jedi were done by ILM, but Star

Wars' troublesome negative needed a professional hand. He did

the work at Burbank's IVC, which, as it happened, was located

downstairs from John Lowry's offices. Dean used IVC's da Vinci color

corrector in 4:4:4 mode, with a CRT monitor that accepted 4:4:4.

[41] One of the bigger issues was smoothing out

the film densities, an issue Lowry would struggle with as well. "The

sands of Tatooine showed multiple colors in the same shot, really

just due to film handling and aging," Dean says. "On any

particular shot in the film, you can color correct one frame, and

two frames up, the sand's a different color. We counted on Lowry's

unique technology to even out those types of fluctuations and then

go back and do a final color tweak." [42] Videography writes: "The film was provided to

Dean on SR tape one reel at a time. Dean's corrected versions would

be sent back to ILM in Northern California, where Lucas himself

would view the footage on a DLP cinema projector, sometimes offering

comments for further color adjustments." [43]

From here, John Lowry and his company stepped in.

"We'd done a lot of work on the films prior to going to John," says

Lucasfilm's VP Jim Ward, "re-mastering them in high-def,

down-converting them into standard def, and re-color timing them. We

actually took a cleaning pass through Industrial Light and Magic, as

well, but then ultimately took them down to John to make them

pristine." [44]

"We sent one of our 6-terabyte servers up to

Skywalker Ranch in San Rafael, California, where they loaded it with full RGB [red,

green, and blue] data without having to go through the component

output that tape masters would

demand," John Lowry said. "We processed those images, cleaned

them up, and sent them back in little packages of discs. The net

result was that we never lost a bit in the process of moving all the

data back and forth." [45]

Photo-chemical restoration, as the 1997 release

mainly was, had become a thing of the past by 2004, and digital

technology offered a treasure trove of tools to offer repairs never

before available, such as digitally painting out scratches and dirt.

Lowry Digital Images, headed by founder John Lowry, had become one

of the leading companies specializing in digitally cleaning film,

using a unique computer program that was able to mathematically

paint out dirt. Its early efforts were controversial--the first

release was the 2001 DVD of Citizen Kane, and it looked as

clear as a mirror. Which was not the way it should have looked.

Grain is a part of the film image--it literally is the

image, just as pixels are what a digital image is composed of--and

is part of any film's aesthetic; the computer algorithm could not

distinguish between dirt and dupe grain, and the actual emulsion

grain, and as a result the final product looked like it was shot on

video.

Lowry refined its technology in the years since

then, having shown improvement in their handling of Lucasfilm DVD

releases of THX-1138 (another Lucas special edition) and

the Indiana Jones trilogy, both released in 2003, and when they were

hired to do the Star Wars trilogy in early 2004 [46] they were confident they could deliver.

Lucas might not have minded if they weren't--he was looking to go

beyond simply getting the film back to its prestine state. This is

evident in the hiring of Lowry in the first place--the negative had

been thoroughly cleaned in 1995 by professional film

restorationists. Though one can still see plenty of emulsion grain

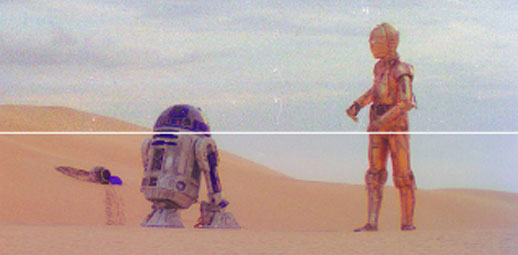

on the 2004 release if you look closely, the image is indeed

much cleaner than it should be, and Lucas had them artificially

sharpen both the entire image and select portions (i.e. composites

where certain elements might have been photographed soft--such as a

long shot of C-3P0 and R2-D2 walking on Tatooine in Return of

the Jedi) [47]. Digital technology also

allowed Lowry to paint out by hand many instances of film damage

that it wasn't possible to address in the photo-chemical days of the

first Special Edition.

Lowry spent a hasty three months working on the

entire trilogy. The Star Wars.com website reported: "At the Lowry

Digital Images facility, over 600 Macintosh dual-processor G5

computers utilizing over 2400 gigabytes of RAM and 478 terabytes

(over 478 million megabytes) of hard drive space processed each of

the classic Star Wars films for over 30 break-neck days to

create the stunning new versions fans will see in the Star

Wars Trilogy DVD set." [48] Star

Wars, in particular, was problematic and required some

specially modified software to handle the dirt issue. "We had to do

some special work on these, actually build some different algorithms

to try to deal with the incredible dirt levels and scratches," John

Lowry stated. "It was somewhat overwhelming." [49]

Lowry reports that they discovered thousands of

grains of sand embedded in the image in the Tunisian scenes,

which initially gave their computer algorithms

trouble. Though as a camera assistant I have a hard time

believing that sand could have gotten lodged in the microscopic

spaces between the film layers considering the rigorously clean

conditions camera assistants subject film to while loading and

changing; probably, these are dust blowing in the photographed

atmosphere or perhaps even trapped in the body of the camera. In an

interview with Sound and Vision, Lowry says: "In the first

movie, you have C-3P0 and R2-D2 walking across the desert, and I

think half of that desert sand ended up in the camera. It was

unbelievable. One technique we use is where you look at the frame

before and the frame after to determine what is dirt on the frame in

between. When you have as much dirt as this, though, the before and

after frames have the same damn dirt--and more. It's really hard for

the program to separate what's dirt and what's image. It led to a

lot of extra work--run it again, check it again, multiple passes, a

lot of hand work at the end." [50] Most surface dirt would have been washed away in

the 104-degree sulphur bath the negative was wrung through in 1995,

but still, the frequent handling of the film left enough dirt,

dust and damage that couldn't be washed out that John

Lowry called it the worst example of dirt in a film that he had

seen.

In other shots, scratches had resulted in a

wet-gate transfer done, where the film is printed in a special fluid

that fills in fine scratches, but sometimes can lead to extra dirt

accumulating and softening the image. At the same time, however,

Lowry sharpened the entire film slightly beyond what had been

originally photographed. "We cleaned it up, matched scene to scene,

sharpened it end-to-end, reduced the granularity and got rid of the

flicker and all the wear-and-tear things," Lowry says. [51]

They further cleaned up the opticals, which had

already been improved for the 1997 release. "Opticals are a little

soft, and much grainier, because there are two more generations on

film, and there's a little more contrast," says Lowry. "We try to

match those scenes perfectly so they don't telegraph that

something's going to happen, a light saber sequence, for example, by

showing a change in picture quality. We removed that extra grain,

reduced the contrast, and got the sharpness to match the prior and

following scenes." [52]

The final result is strikingly different from the

original photography: a totally new color palette, less grain, and a

subtly oversharpened image. It is sometimes thought that the Lowry

Digital Images restoration has resulted in a better picture than

even the original photography had, and while this is true it is not

quite as drastic as some may think in most respects.

Star Wars is thought to be natively grainy, but in fact it

was photographed very cleanly on a fine-grain stock, and most

of the "grain" seen throughout its life is either dupe grain or dirt

that is foreign to the original negatives; to be sure though, a lot

of the original grain was scrubbed off, either deliberately or

mistakenly. This photograph is very telling: while it also reveals

damage and scratching, plus some shimmering and flickering effects

that are the result of photochemical aging, this shot (which has

been color-corrected, it should be noted) still displays much

more of a grain "look" than the generally clean Lowry

result.

Lowry claims that these desert scenes had

thousands of dirt instances in each frame, but it is difficult to

distinguish which is grain and which is dirt. A high quality scan

would have probably aided making this distinction more accurate, if

indeed it needed to be made moreso. An article from Studio

Daily had this to say:

"The Lowry Digital way of

restoration isn't without its controversy, and both Lowry and

[company president] Inchalik acknowledge the rumblings. The

crystal-clear imagery turns classic Hollywood films into a brand-new

viewing experience. Where's the thin line, for instance, between

correcting for the grain introduced by multiple generations of film

prints and the excision of so much grain that the image resembles

video?

But Inchalik's response makes the Lowry

Digital Image position clear. "Is all grain sacred?" he asks. "I

appreciate grain, but sometimes it's a limitation. If I'm handed

something three generations old, it's silly to preserve that level

of grain. We should get back to the quality analogous to the show

print seen by the director and cinematographer." But, he notes, the

decision to restore the Lowry Digital way is made by clients. Lowry

Digital Image is betting that those images will open up a new market

for them in DIs. "The images people will see will, pleasantly, cause

waves," predicts Lowry." [53]

On the other hand, Director of Photography

Gilbert Taylor photographed Star Wars to be gauzy and

slightly soft-filtered--this was at the request of Lucas. In

certain shots in Tunisia, Lucas insisted on using filters, even

pantyhose over the lens, to get an intentionally soft image; Taylor

disagreed with this approach, feeling the desert already gave a soft

look, but did it anyways. [54] The sharpening to

Star Wars that Lucas in 2004 insisted on, especially in the

desert scenes, often betrays this deliberate look, especially ironic

since it was Lucas who initially insisted on it in 1976. John Lowry

said in an interview with Sound and Vision: "On each of

these movies, George would look at a scene and ask us to sharpen

something a little--almost scene by scene. We can do that

beautifully without putting edges on things. It's very different

working with the director who created the movie you're restoring. It

gives us a whole new sense of the creative objectives and exactly

what path to take--how much sharpness, how much grain to leave. All

decided by George." [55]

Another flaw that has been speculated to be the

result of the Lowry process is the disappearance of the star

fields--if one looks at the space star fields, most of them have

either been re-done or have had many of the stars erased. This could

be a result of the crushed blacks on the color-timing, or because

the Lowry software couldn't distinguished between stars and dirt and

erased them, resulting in ILM having to create new ones. This could

have also been enacted for purely aesthetic reasons, but this seems

very unnecessary.

Sound and Vision also questioned John

Lowry about the unusual low-resolution of the release, a decision

made by Lucasfilm and not his company, but he rather dodged the

issue by alleging that the opticals were at less than 4K due to

generational loss, but surmised that Lucas might re-do the entire

process for an HD release. As it turns out, he hasn't, as the film

has been shown many times on HD broadcasts using the HD master,

although a re-do for Blu-Ray seems possible but unlikely. The

exchange:

"Sound and Vision: So the Star

Wars films were processed at high-def, but not at the 4K level

--four times high-def resolution--that you've been using for some

other films?

John Lowry: At

high-def, yes.

SV:Why was that?

JL:The challenge

with these films is the amount of special effects in them. Our

concern was whether the effects were done to true 4K standards.

Whenever anyone lit up a lightsaber, it was done with an optical

effect, and all of the opticals at the time were done on film--there

were no digital effects. So every time you go to a lightsaber scene,

bang, you drop two generations of film. It gets grainier and, as

it's going through an optical printer, you have different

characteristics in terms of contrast. And those are things we have

to match up with the scenes immediately before and after. It took a

lot of effort to match precisely the granularity, the contrast, and

the sharpness. They flow very nicely now and, frankly, in the

original movies, there was a distinct change. We were able to

eliminate that change, and to me that's a very strong contribution

to the storytelling process--removing something that prevents an

audience from being drawn in.

SV:But the high-def digital material was

fine for the standard-resolution DVD release?

JL: Yes. My guess,

knowing George, is that maybe he'll be back when they do the

HD-DVD." [56]

One unusual feature of this is the mention of

lightsaber opticals losing generation quality--but these shouldn't

be optical composites. In creating the 2004 DI, Lucasfilm

re-rotoscoped all the lightsabers digitally from the looks of

things, which would mean they went back to the raw negatives and not

the final composites. Perhaps the negative in these scenes was

simply dirtier because it had been run through the optical printer

and picked up more wear. Videography says that they weren't

actually using the O-neg but rather the 1997 Special Edition

negative (the IN, I must presume?) because that was the only one

that had the new visual effects work--but the O-neg would have had

the new CG shots cut in, and why would they need to color correct it

so heavily if it was the YCM Labs-corrected IN? Every other sources,

including stills from their workings, and articles published by

Lucasfilm (starwars.com) indicate that it was the O-neg, and

not the the SE IN.

Perhaps what was meant was that they were working

from the SE-conformed O-neg, which is indeed the case. In further

discussion of negatives and composites, it is notable that Lowry's

talk about extra dirt on composites probably refers mainly to

Empire and Jedi. According to American

Cinematographer, ILM did their work on Star Wars 's

Jabba scene using the interpositive (since the O-neg was lost when a

16mm dupe was made for the 1983 documentary From Star Wars to

Jedi), and they learned to digitally reduce the extra grain so

successfully that they found it was easier to do all the CG

enhancements in the sequels from IPs (except when scenes were

digitally composited--in Empire, the entire walker sequence

was re-composited, as was at least portions of the asteroid chase

judging by footage from SE documentaries).

Videography reports that "Finished footage

was shipped to Lucas for review on the 250GB hard drives from

Lowry's network," [57] just as John Lowry

earlier noted ("disk packs"=hard drives). When the

Lucas-approved newly refurbished film and its two sequels were

released in September of 2004, they were met with enthusiastic sales

and praise for Lowry, but also criticism for being further altered

and for the harsh coloring and visual glitches.

Back to the

Future

So, then, is this the final state of Star

Wars? Judging by the trajectory of technology, it seems

inevitable that Star Wars will end up as virtual negative.

The question is: will there be further editions, and will Lucasfilm

ever go back to the source--to the negatives? The answer to the

first question is perhaps, if only to correct the errors of the 2004

edition--not just to picture, but to sound (swapped audio channels),

and visual effects (colorless explosions, dull lightsaber

cores)--and because it seems inevitable that Lucas will continue to

enact minor tweaks (for instance, Episode I has been given a digital

Yoda, still unreleased officially though seen on the Episode III

DVD). Possibly these may be made for the Blu-Ray release, or the

in-progress 3-D release, or possibly not. The second question is a

harder one to answer. Lucas seems perfectly fine with the current

version, seeing as he's re-released it on video twice, broadcast it

all over TV and in HD, and theatrically shown it at numerous

screenings. He also approved of the final product himself, of

course.

However, even clues in the current master

indicate Lucas used poor judgment in 2004 and may re-tweak the

image. The blockade runner's cool blue tone stands in stark contrast

to Revenge of the Sith, released a year later, which

reverts back to the original white tone, indicating a nullification

of the 2004 decision. And while Lowry acknowledges that the

2004 master was acceptable only as a standard-def project, Lucas has

indicated that that master is to be the "for all time" version. [58] He even stated, when asked why he didn't spend

money to refurbish the original, that millions of dollars had been

spent to make the Special Edition, and that his work restoring the

films was basically done. [59] It would not

be surprising if any further tweaks, or the Blu Ray release, used

the HD master of the 2004 release as a base. ILM's 2004 visual

effects work on the film--such as new shots at the end of Return

of the Jedi and a brand new version of Star Wars'

Jabba scene--were done using the HD scan, so if the 2004 master is

thrown out, so would all the revision work that went with it, which

means we may be stuck with it. That Lucas shot his last two prequels

in the same resolution indicates he is more than comfortable with a

1080p master of his films.

However, it is also incredibly hard to imagine

that Star Wars will never be restored to its original

version. Perhaps it will take Lucas' passing to see this enacted--or

perhaps not, given that he allowed the original versions to be

released on DVD in 2006, even if they were just Laserdisk ports. In

any case, I would be willing to bet a good amount of money that in

some years in the future efforts were made to somehow save the

original version of Star Wars--from Lucas himself, it may

seem, as his Special Edition would have to be somehow worked around

in gathering original elements. The negative could be re-conformed

to its original configuration, using the original, saved pieces, but

this is problematic due to handling issues (and losing more frames).

When Robert Harris restored Godfather last year, he had to

do it entirely digitally, saying that if any pin-registered

mechanism were to touch the negative it would crumble. [60] In Star Wars' case, using scans of

the separation masters is perfectly viable, and though IPs and

Technicolor prints are not ideal for masters they could be usable if

cleaned up digitally. Perhaps the easiest option would be to simply

follow the 1997 restoration pattern but in the digital

realm: scan the negative in 8K, then scan the stored pre-SE

shots or re-comp them, and fill in any damaged areas with IPs or

separation masters, reconstructing the original cut, then digitally

remove dirt and damage, and finally use a Technicolor print as a

color reference for the Digital Intermediate created. Such a product

would be theatrically viable, as pristine as when it had been

shot, and 100% faithful in image and color to the original

release.

The pricetag of doing a project like this would

likely be under a million dollars. Jim Ward claims that Lucasfilm

sold $100 million in DVDs in a single day when the refurbished

Star Wars films came out in 2004, [61] and

while this figure might not be replicated (though in my opinion it

probably would, if given a comparable marketing campaign) clearly

there would be worthwhile profit. One day, I predict this process

will happen, but that day does not seem to be anywhere in the near

future. It will remain to be seen if the

negative to Star Wars is in a salvageable state by the time

this happens or if it has become a brittle relic, faded to black and

white. It wouldn't be the first time the negative of a famous film

has been lost--Criterion's restoration of Seven Samurai,

for instance, does not work from a negative, nor did the gorgeous

35mm print of Rashomon that toured theatres this year. With

fine-grain masters, IPs, and Separation masters available, the

negative need not be the only source for a new

master.

Backlash has, of course, occurred because of all

this drama. The last dedicated release of the original version was a

Laserdisk and VHS in 1995 (using the 1985 IP, which was then

mastered in THX, according to Into the Digital Realm--the

in-progress restoration couldn't be used for this release because it

was still in-progress). By 2006, originaltrilogy.com had petitioned

over 70,000 signatures to get the original versions released, and

while the Laserdisk-port release of that year was at least admission

of defeat of Lucas' crusade to erase the originals from existence,

it also frustrated fans and experts alike, especially since the

release wasn't even anamorphic (as the Laserdisk wasn't). When a

letter-writing campaign reached Lucasfilm they responded by saying

that the Laserdisk was the best source for the originals [62] --which it would be without having to spend

money, that is. Robert Harris, the man who had hand-restored

Vertigo and Lawrence of Arabia, and later The

Godfather, went on record saying he knew there were

pristine 35mm elements available for use, and offered his

services to restore the film [63].

Lucasfilm did not respond. The efforts of fans and professionals

like these will probably result in the aforementioned restoration at

some point, if only for the callousness of making money, but it

seems that day is not today.

The story of Star Wars' negative is both

the story of advancing technology and the story of Lucas' ego.

Showing how fragile negative film can be, how all sorts of

old-fashioned tricks and the most advanced of analog technology was

used to photo-chemically restore the elements, which were then

embellished by select digital pieces in the infant

technology, like some kind of emerging cyborg; by 2004, the

film had been entirely consumed by digital technology, existing only

as a digital negative. At the same time, a crusade of revisionism

took over, moving from a project to preserve Star Wars so

that future generations could see it, to an enhanced anniversary

celebration for the fans that Lucas could use as an excuse to play

with emerging digital technology, to finally a consummation of his

prequel storyline and a nail in the coffin for the original version

that so many had loved and that had given him his empire in the

first place, while the quality of the negative itself seemed

perpetually sliding downward in resolution.

Note: in the July 1977 issue of American

Cinematographer: "It was decided to use black and white

three-color separations for all primary images in the composites.

The emulsion of 5235 color separation stock has a wide contrast

latitude and grain definition which is superior to 5243 color

interpositive: it is the best choice for quality." So the raw

elements were shot on 5235; although apparently used as a separation

shot, Kodak lists it as an intermediate. This statement may also

suggest that 5243 was then what the composite of the 5235 elements

were printed on.

[1] Hearn, Marcus. The Cinema of George Lucas. 2005.

p.183

[2] Vaz, Mark Cotta and Duigan, Patricia Rose.

Industrial Light and Magic: Into the Digital Realm. 1997.

p.291

[3] Vaz, p.290

[4] Interview by Mr. Showbiz, 2000,

http://mrshowbiz.go.com/interviews/299_2.html

[5] Oprah, February 1997

[6] Vaz, pp.290-1

[7] see the note on:

http://secrethistoryofstarwars.com/jabba.html

[8] Magid, Ron. "An Expanded Universe," American

Cinematographer, February 1997.

[9] Vaz, p.291

[10] Magid, Ron. "An Expanded Universe," American

Cinematographer, February 1997.

[11] Vaz, p.288

[12] Vaz, p.288

[13] Vaz, p.287

[14] Vaz, p.287

[15] Vaz, p.288

[16] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[17] Vaz, p.288

[18] Vaz, p.287

[19] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[20] Vaz, pp.287-8

[21] Vaz, p.288; Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars

Sequels," American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[22] Vaz, p.288

[23] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[24] Vaz, p.288

[25] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[26] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[27] Vaz, p.288

[28] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[29] Vaz, p.289

[30] Vaz, p.289

[31] Magid, Ron. "Saving the Star Wars Sequels,"

American Cinematographer, February

1997.

[32] Vaz, p. 289-90

[33] Star Wars, The Magic and Mystery,

1997

[34] Vaz, p.290

[35] for instance, American Cinematographer, in its

February 1997 issue, reports that the trilogy's restoration costs

$10 million. Whether this is for all three films, for just the

salvaging of the negative, for just the enhancements, or for any

combination or variant of the above is not

clear.

[36]

http://www.starwars.com/episode-iv/feature/20040916/index.html

[37] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004.

[38]

http://www.starwars.com/episode-iv/feature/20040916/index.html

[39]

http://www.starwars.com/episode-iv/feature/20040916/index.html

[40] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004.

[41] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004.

[42] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004.

[43] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004.

[44]

http://www.apple.com/ca/pro/film/lowry/starwars/index.html

[45]

http://www.soundandvisionmag.com/features/671/restorer-of-the-star-wars-trilogy-and-thx-1138-john-lowry.html

[46] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004.

[47]

http://www.apple.com/ca/pro/film/lowry/starwars/index2.html

[48]

http://www.starwars.com/episode-iv/feature/20040916/index.html

[49]

http://www.apple.com/ca/pro/film/lowry/starwars/index2.html

[50]

http://www.soundandvisionmag.com/features/671/restorer-of-the-star-wars-trilogy-and-thx-1138-john-lowry.html

[51]

http://www.apple.com/ca/pro/film/lowry/starwars/index2.html

[52]

http://www.apple.com/ca/pro/film/lowry/starwars/index2.html

[53]

http://www.studiodaily.com/filmandvideo/tools/otherways/4755.html

[54] Williams, David E. "High Key Highlights: Gilbert

Taylor BSC," American Cinematographer, February

2006.

[55]

http://www.soundandvisionmag.com/features/671/restorer-of-the-star-wars-trilogy-and-thx-1138-john-lowry-page2.html

[56]

http://www.soundandvisionmag.com/features/671/restorer-of-the-star-wars-trilogy-and-thx-1138-john-lowry.html

[57] Hurwitz, Matt. "Restoring Star Wars,"

Videography, Vol. 29, No.9, 2004 .

[58] see his statements to the Associated Press in

September 2004:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6011380/

[59] see above.

[60] Argy, Stephanie, "Post Focus: Paramount Restores

The Godfather", American Cinematographer, May

2008

[61]

http://www.starwars.com/episode-iv/news/2004/09/news20040922.html

[62]

http://www.originaltrilogy.com/Lucasfilm_PR_response.cfm

[63] see http://digitalbits.com/#mytwocents/ for

May 19,

2006.

11/03/09

Web site and all contents © Copyright Michael

Kaminski 2007-2009, All rights reserved.

Free

website templates |

|