|

Home

FAQ

The Book

Articles

Links

Contact

|

|

In Tribute to Marcia Lucas

Biographer Dale Pollock once wrote that

Marcia was George Lucas' "secret weapon." [i] Most people are aware

that George Lucas was once married, and probably some are aware that

his wife worked in the film industry herself and edited all of

George's early films before their 1983 divorce. But few are aware of

the implications that her presence brought, and the transformations

her departure allowed. She was, in many ways, more than just the

supportive wife--she was a partner as

well. "Not a fifty percent partner," as she herself admits, but

nonetheless an important one, and the only person that Lucas could

totally confide in back then. Today, she has been practically erased

from the history books at Lucasfilm. Looking through J.W. Rinzler's

Making of Star Wars, she is mentioned only occasionally in

passing, a background element, and not a single word of hers is

quoted; she is a silent extra, absent from any

photographs and only indirectly acknowledged, her contributions

downplayed. In the documentary Empire of Dreams, she is

barely even mentioned in passing, except when the narration states

that she edited the film and Lucas says he "got divorced as

Jedi was complete" in the last two minutes of the

supposedly-definitive documentary. Other products fare not much

better, since many of them are published through Lucasfilm; her

entire existence has nearly been ignored. Marcia Lucas, the "other"

Lucas, has basically become the forgotten Lucas.

Perhaps it is the painful memories of the final

unhealthy years of their marriage, during which Marcia finally left

Lucas for another man and got a large cash settlement, that has

prompted him to essentially never speak of her again. Indeed, it is

a rare day when her name is uttered by him, even as "my wife" and

other impersonal labels. Even in the 70s and 80s she was defined not

on her own merits but by her relationship to George--she was not just Marcia, she was "Marcia, the

wife of George Lucas", forever overshadowed. Yet nonetheless, Lucas

and every fan of his films owe her a debt of gratitude. She was an

instrumental part in the shaping of his scripts, and the primary

force behind their final form in the editorial stage, where she cut

the pictures herself. But more than that, she had a prolific and

successful career of her own as an editor, and was a key figure in

the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s; a secondary figure,

perhaps, yet unlike other secondary figures such as Walter Murch and

John Milius, her existence has been almost entirely

forgotten.

In this article I will be taking a look at the

life and career of Marcia Lucas (nee Griffin), and the impact and

influence she had on her husband's films.

Such a piece has never been attempted before,

whether in print, in video, or on the internet. Even on web pages

all one finds is a couple of piecemeal trivia bits; forget

about an actual quote from the woman herself or anything more

than a handful of sentences. This is the first-ever

biography of Marcia Griffin, and the reason why I decided to

undertake such a piece. Marcia was a charismatic and talented woman,

who had a significant--but basically

unappreciated--influence on 1970s

filmmaking, both directly and indirectly. In the direct sense,

she was the primary picture cutter for her husband, George Lucas, as

well as Martin Scorsese, in addition to the other films she edited

and assistant edited. Indirectly, she was part of the social scene,

as both Lucas' spouse and as a creative collaborator herself, and

part of the inner circle of the influential "Movie Brats". Her

opinions, her suggestions and her interactions formed and shaped the

collective movement, and her subtle influence in this respect is

especially unnoticed. She also, as I alluded to earlier, was a

profound part of the cinema of her husband, who himself is one of

the most successful and influential filmmakers in history. In fact,

the only Oscar the Lucases ever earned was hers, for editing

Star Wars .

Creating both a portrait of Marcia Lucas

and assembling a compelling biography of her and her work is a

difficult task. Whether in books or magazines, no matter the

publication, one finds only brief mentions of her, always as an

addition to the main piece about her husband, supplemented only by

the occasional rare glimpse into her thoughts and feelings; she

comes to us fragmentary, and often only in publications that are

obscure today because of their age. Author Denise Worrell, who was

one of the last journalists to speak to her before her divorce from

Lucas and subsequent disappearance, introduces her in 1983, when

Marcia was closing in on forty years old and had basically retired

from the industry to become a full-time mom:

"Marcia Lucas, thirty-seven, is spunky and

unspoiled. She wears a huge diamond on her left hand but often has

her brown hair in a ponytail on the top of her head, and dresses in

blue jeans, sweat pants, sweatshirts, and tennis shoes. She uses the

adjective real a lot." [ii]

Such a description, brief as it is, is

rare by comparison to most references, which gloss over her

existence or merely acknowledge her in passing. Because of this

dearth of sources, any survey of her is by nature somewhat limited,

and very George Lucas-oriented. Dale Pollock's Skywalking: The

Life and Films of George Lucas, published in 1983, is the

wealthiest source of info, and treats her as an active partner with

Lucas, even recalling Marcia's background history, and includes a

swath of interviews with her. Peter Biskind's Easy Riders,

Raging Bulls, published in 1997, includes participation from

her as well, and the only participation from her after the 1983

divorce, which affords us a unique view of an older Marcia Lucas

reflecting retrospectively on events (often with bitterness, it

seems). The remainder of her comes in cubist form by assembling

small sections from smaller publications; Denise Worrell's piece

contains involved, but still limited, participation from Marcia,

while she is heard from here and there in other publications such as

Time and People. John Baxter's book

Mythmaker (also titled George Lucas: A Biography)

provides her some attention, while she is briefly discussed in

A&E's Biography episode on George Lucas. One of the

only quotations from her in an actual Lucasfilm publication is in

John Peecher's 1983 The Making of Return of the Jedi, where

she shares an anecdote about editing the original Star

Wars.

Yet from this relatively small sampling, a

surprisingly detailed and compelling picture emerges, more than

enough to provide us insight and appreciation. "I love editing and

I'm real gifted at it," she stated in 1983. "I have an innate

ability to take good material and make it better, or take bad

material and make it fair. I'm compulsive about it. I think I'm even

an editor in real life." [iii] Today she has disappeared, and

routinely has refused to talk to press; my own efforts to contact

her, through a family connection, were unsuccessful, though she

wrote to me briefly to offer a small handful of corrections. At the

time of this writing, she would be about sixty-five years old. I

hope that the following suffices as an informed overview of Marcia

Lucas, and recovers her from the dustbin of

history.

Early

Life

Marcia Lou Griffin was born in 1947 according

to author Peter Biskind, but most publications state she is only a

year younger than George Lucas, who was born in 1944. Her date

of birth is not quite as significant as the location--Modesto, California. The sleepy town that was

home to about 20,000 people at that time was also the closest

hospital to Stockton Air Force, where Marcia's father was stationed,

and so, as if joined by fate, Marcia was born in the far-flung town

where Lucas himself lived. However, their paths did not cross at

that moment, and Marcia was in all likelyhood gone from Modesto as

quickly as she arrived. Marcia's father was a career military man,

and often had to move his family when he was re-assigned a new base.

His relationship with Marcia's mother, Mae, was "off-and-on"

according to biographer Dale Pollock, but they finally divorced for

good when Marcia was two. Mae took off for North Hollywood with her

two daughters, where the girls lived with their grandparents. When

Mae's father died, they moved into a small apartment in his

neighbourhood, and Mae got a job as a clerk for an insurance

agency.

Marcia's childhood was not the quaint, stable

one that her future-husband was blessed with, at the time still

blissfully passing through life in Modesto. Her family worked hard

to put food on the table, which was not easy for a working, single

mom, as Mae was. Marcia remembers the period as "a hard life" [iv].

The Griffin family didn't have the luxury of much money, and most of

Marcia's clothes were hand-me-downs. "It wasn't a sad, bad time,"

she says. "We had a lot of love and a very supportive family. But

economically it was very hard on my mother." [v] Marcia's father had meanwhile re-married and

was stationed in Florida, and, as Pollock reports, "financial aid

was not forthcoming" from him. Marcia, in fact, never knew him while

growing up. She went to live with him when she was a teenager, but

this never worked out; she left after two years, returning to North

Hollywood to finish high school, hoping to go on to college. Yet

Marcia felt responsible for her mother, who worked so hard to give

her and her sister a good life, and so she began working days and

going to school at night. This bold work ethic would characterise

both Marcia's life and career, but also her

success.

Marcia took night school courses in chemistry,

but by day she worked at a mortgage banking firm in downtown

Los Angeles. A boyfriend of hers worked for a Hollywood museum and

wanted to hire her as a librarian to catalog all the donated movie

memorabilia. Unfortunately, librarians had to apply to the

California State Employment office in order to work, and so she was

instead sent to the Sandler Film Library, which was looking for an

apprentice film librarian without any experience. It only paid $50 a

week--less than she made at the bank--but

she took it anyway. So began the editing career of young Marcia

Griffin. "That's how I started working in film," she says. "I just

walked in off the street." [vi] Dale Pollock describes:

"It was hard work. Marcia took orders for film

footage that producers required, such as shots of a 1940s Ford

turning left on a country road at night. If the material fit the

scene, she ordered the required negative prints, a highly technical

job that Marcia immediately grasped. She also found herself drawn to

the instant gratification of editing." [vii]

By the time she was twenty she had worked her

way up the ladder to assistant editor, but the road had been, and

would continue to be, a hard struggle. Breaking into the film

industry was tough for a woman in the mid-1960s, and like any

technical job the best gigs all went to men. She was lucky she was

in editing in the first place--most film

related positions, such as camera or lighting, were quite literally

all-male; film editing, since the birth of the medium, was the one

area where women were allowed in, since it was initially thought of

as a task comparable to sewing or cooking. Yet most

professional editors were nonetheless men. Marcia, however, was

driven and talented, determined to climb the union ladder

through her eight-year apprenticeship--commercial editors could make

$400 a week, a fact that she didn't forget, hopeful to have a

stable life for once. She cut trailers and promos to keep her skills

sharp, but nonetheless advancement was slow. "I thought I was a

tough cookie, but I didn't realise what I was up against," she

admits. [viii] She was told girls couldn't lift the heavy film cans

that the reels came in, or that editors used foul language

unsuitable for a girl. Marcia nonetheless forged ahead. "I would have

cut films for free because I enjoyed it so much," she insists.

[ix]

Verna Fields, one of the few respected women

editors in the industry at that time, had a job for Marcia in 1967.

Fields often did business with Hollywood film libraries and asked

Sandler Films to send her an assistant editor to help on a small

project she was working on; it was a government-funded documentary

on President Johnson's trip to the far east for the United States

Information Agency, and there was so much footage coming in that

Fields needed an additional assistant. Fields had hired a bunch of

film school grads from USC to cut the picture, and Marcia was

assigned to work with one of them, a young man named George

Lucas.

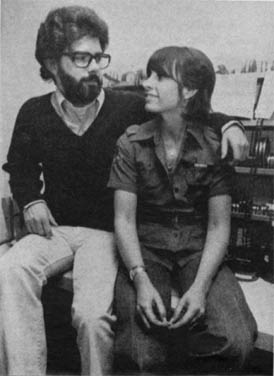

Locked in a small editing room together, they

seemed like an unlikely pair, George shy and introverted and Marcia

bold and outgoing. "Marcia had a lot of disdain for the rest of us,"

Lucas remembers, "because we were all film students. She was the

only real pro there." [x] Yet Marcia too felt a sense of

intimidation which she didn't reveal, for she had never graduated

from the night classes she started taking a couple years earlier,

and felt intellectually inferior to university grads. But there was

something about the young brunette that George found compelling;

eventually he asked her to go to a screening of a friend's film at

the American Film Institute with him. "It wasn't really a date," he

says. "But that was the first time we were ever alone together."

[xii]

The awkward and closed-off Lucas was slow to advance,

however. It was weeks before they managed to have a serious

conversation, and even more weeks before they ever had a real date.

Lucas had also never had a serious relationship before; his

girlfriends usually only lasted a few dates. Slowly but surely,

however, Marcia drew him out of his shell enough to ask her out.

Their dates were usually at the movies, and they both

disliked the Hollywood social scene, content with spending time at

their apartments arguing about the film industry. The casual

atmosphere at Verna Fields' San Fernando editing house provided a

comfy environment for their relationship to grow in. Dale Pollock

writes:

"Marcia enjoyed being with George. He seemed so happy,

humming and tapping his foot to the ever-present radio music in the

editing room. When one of the other female editors asked her what

she thought of the shy young student, she had a ready answer: 'I

think George is so cute. If only he weren't so small.' Marcia

thought she outweighed George, who was as thin as he was short

(actually he is taller by a few inches). She loved his nose, set on

a handsome face with good features. But Lucas was hard as hell

to draw out in conversation. He might discuss the films he was

working on but rarely did he bring up personal matters."

[xii]

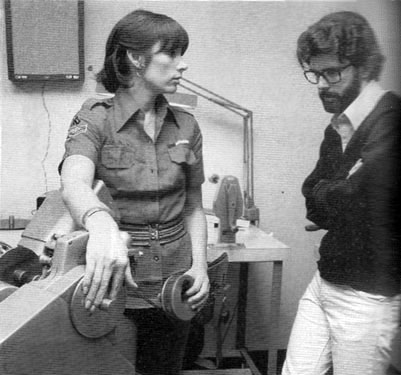

The Fields house also allowed for a good learning atmosphere

for George. While Lucas is well known for his editorial skills, and

immediately had an instinctive talent for editing even as a film

student, his first professional mentor outside of film school was

Marcia. They were paired up by Fields because he was the least

experienced editor and she was the most experienced assistant.

Pollock writes, "Marcia knew more than George about editing

technique, but her job was to help him." [xiii] She would often look

over his shoulder to make sure he was doing alright and lend a

helping hand when needed. She was also often impressed by him,

saying: "He was so quiet and he said very little, but he seemed to

be really talented and really centered, a very together person. I

had come out of this hectic commercial production world and here was

this relaxed guy who threaded the Moviola very slowly and

cautiously." [xiv]

Lucas for his part respected her as an editor. He says about

filmmaking, "It really becomes your life, and it was Marcia's life,

too. That's one of the reasons our relationship works--we both love

the same thing." [xv] Marcia also won Lucas' respect due to

her sense of independence. "Marcia and I got along real well," he

says. "We were both feisty and neither one of us would take any shit

from the other. I sort of liked that. I didn't like someone who

could be run over." [xvi]

Marcia felt that their relationship was kept in check by a

very real sense of balance."I always felt I was an optimist

because I'm extroverted," she says. "And I always thought that

George was more introverted, quiet, and pessimistic." [xvii]

Biographer Dale Pollock concludes that she supplies the

aggressiveness that Lucas lacks, while his low-key

temperment softens her abraiseness. "We want to complete

ourselves, so we look for someone who is strong where we're weak,"

Marcia says. [xviii] Lucas agrees: "Marcia and I are very

different and also very much alike. I say black, she says white. But

we have similar tastes, backgrounds, feelings about things, and

philosophies." [xix]

Marcia

surprised and impressed Lucas' friends as well. Most of them met her

when she was in the cutting room at USC, helping George

edit his short film The Emperor. [xx] "She was a knock-out," John Milius remembers. "We all

wondered how little George got this great looking girl. And smart

too, obsessed with films. And she was a better editor than he was."

[xxi] Marcia says that George has "a very childish,

silly, fun side, but he doesn't even like me to talk about that

because he is so intensely private." [xxii] His repressive

introversion even put off Marcia at times. "I'm capable of envy and

jealousy--I've felt those emotions throughout my life, and I think

they are normal emotions. But they are emotions George doesn't feel.

I honestly have never seen George envious or jealous of anyone."

[xxiii]

George kept quiet about his relationship with his parents,

but eventually the Lucases came down for a student film screening

where they finally met Marcia. Lucas' mother, Dorothy, remembers,

"The minute I saw them together, I knew that was it." [xxiv] That

Thanksgiving, he took Marcia to Modesto for a formal introduction to

his family. Marcia recalls: "He

was very, very open when he was with his family...It was the most

open I had ever seen him. He was open with me, but as soon as it got

beyond just the two of us and our intimacy, he was again very

quiet." [xxv] She

was especially touched by an exchange she overheard between George

and his brother-in-law Roland. "You know, Marcia is the only person

I've ever known who can make me raise my voice," he said. Roland

grinned and replied, "That's great kid, congratulations--you must be

in love." [xxvi]

As

their relationship grew, Marcia had to think about what she wanted

to do with her life. She was happy with staying in L.A. and working

her way up the union ladder as an editor, a comfy and secure living

that she could be content with. But her boyfriend had grander plans

of becoming an independent filmmaker and moving to San Francisco,

and thought they could make it there together. This wasn't exactly

what Marcia had seen for her future, but she did like San Francisco

and was willing to take the risk out of faith in Lucas.

"Everything was a means to an ends," she says about him. "George has

always planned things very far in advance." [xxvii] In the meantime,

Lucas was still finishing up at grad school at USC, and he and

Marcia soon moved into a house together in the L.A. area, on

Portola drive, while George made his final student project--THX

1138: 4EB . After it was shot, Lucas edited it on the Moviola

at Verna Fields' house, sometimes staying up until 3 or 4 in the

morning. It would be surprising if Marcia wasn't involved in giving

him a helping hand there.

Marcia

continued to work in the commercial world while her boyfriend won

student scholarships and eventually an internship on the set of

Finian's Rainbow, directed by a young ex-film school grad

named Francis Coppola. Lucas and Coppola became close friends, and

Coppola hired him as a documentarian for his next film, called

Rain People. The idea for Rain People was that he

would assemble a small crew, rent a few vans and travel across the

country, shooting a low budget movie--a very independent sort of

movie. Coppola's one rule, however, was that the women stayed

home--wives and girlfriends couldn't come along for the ride

(although this rule didn't apply to himself). Lucas had already

been away from Marcia because of Finian's Rainbow, and as

the Rain People crew assembled in New York in 1967 for the

start of the cross-country shoot, Marcia decided she would go there

too. "It was so wonderful and romantic and emotional to see

each other in New York because we had been separated for a long

time," Marcia remembers. [xxviii] Taking the train on a rainy

February day to the next filming location on Long Island, Lucas

finally proposed to her.

"I

was beginning to see where my life was going," Lucas says. "Marcia's

career was in Los Angeles and I respected that. I didn't want her to

give it up and have me drag her to San Francisco unless there was

some commitment on my side." [xxix] This was especially troublesome,

as Marcia's career was just beginning to pick up. If she had made

her way on her own willpower, it is due to Lucas' connections that

she was able to break into the feature-film world. Haskell Wexler,

who had known Lucas since he was a teenager in Modesto, wanted to

hire Marcia to come to Chicago to edit his directorial debut,

Medium Cool. But Marcia had a bit of a dilemma: Rain

People was in need of her services as well. The production had

settled down for a few weeks in Nebraska and editor Barry Malkin

needed an assistant to help organize the footage; Lucas mentioned to

Coppola that his girlfriend was an editor and he agreed to hire her.

Medium Cool promised not only a better salary but much

longer work, and her first credit on a feature--but on the other

hand, assistant editing Rain People in Nebraska would let

her see George. "I'm really going to have to think about this,"

she told him. "Don't you want to be with me? Don't you love me?" he

asked. Finally, she bit the bullet and went to Nebraska. Marcia

reflects: "I was poor, right? Financial security was very important

to me. I wanted to make it my own way. But we were engaged, we were

terribly in love, so I decided to go." [xxx] As it turned out, after

she was done on Rain People, she also ended up cutting

Medium Cool as well--and getting her first feature-film

credit.

Going to San

Francisco

When

Rain People was done, Lucas had miles of film footage that

he had shot for his documentary, called Filmmaker , and it

was Marcia that acted as assistant editor, a fun little project for

them to do together as they planned their wedding, cutting the film

together in their home on Portola Drive.

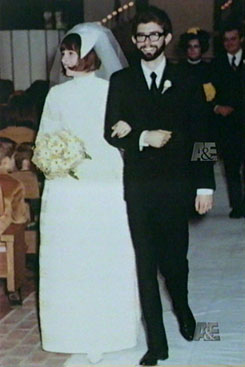

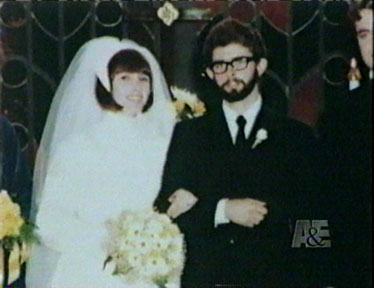

On

February 22, 1969, Marcia Griffin became Marcia Lucas. George and

Marcia were married at the United First Methodist Church in Pacific

Grove, not far from Montery, California. Among the friends in

attendance were Francis Coppola, Walter Murch, Hal Barwood, Matthew

Robbins--and Verna Fields, the woman who had brought them together.

They had a modest honeymoon in Northern California. While they were

there they visited Marin County, just outside of San Francisco; it

seemed to be the perfect place for them to settle down in. Marcia

was able to find a little house in Mill Valley for only $120 a

month. "We were really happy and optimistic," Lucas says, even if

the place was small. "In our lifestyle there were only two rooms we

used, the kitchen and the bedroom. We were in either one or the

other." [xxxi]

Coppola

was founding American Zoetrope in downtown San Francisco, and a lot

of his and George's buddies were joining them there, such as Walter

Murch and John Milius. Marcia's friends and family were still in

southern California. But she liked San Francisco and didn't mind

being there, figuring she would make new friends and find work soon

enough. She began to grow worried as time went by and she remained

unemployed and homesick. Marcia was ready to have a baby, but George

refused the idea, stating that they had only been married a few

months and didn't have a stable income. "He didn't want the extra

responsibility at that time because he might be forced into taking a

job that he didn't want to take," she

says. [xxxii]

Instead,

Marcia played the role of den mother while she waited to find her

opportunity, tending to their Mill Valley home while George set up

American Zoetrope with Coppola. The colorful social scene there at

least made for an interesting time: "There's never a dull moment,"

she says of life under Coppola's leadership. "There are always ten

or twenty or thirty people around, with somebody sitting down and

playing the piano in that corner of the room, and some kids dancing

in that corner of the room, and the intellectuals having a deep

conversation about art in another corner of the room. His life is

just in a constant state of upheaval." [xxxiii] Before the

production company collapsed, Lucas made his first film--THX

1138. The shoot was quick but hard, and Marcia did her best to

support George in whatever ways she could. George's mother

remembers, "Marcia spoiled George terribly when he was making films.

She'd bring him breakfast in bed after the nights he worked late."

[xxxiv] When the shoot was over, George got to work cutting the

film, with Marcia assistant editing. Marcia was more than just a

pair of hands, however, for the two were a partnership more than

anything else; Marcia was always full of good ideas, and she was one

of the few people Lucas actually listened to. At the same time,

however, THX was outside of her tastes; she didn't go for

the strange, abstract filmmaking style Lucas was so fond of, and

ultimately she felt non-plussed by the film because she felt it did

not engage the audience emotionally. This is the essential

difference in approaches between the two Lucases--George more

technical and graphic oriented, while Marcia more character and

storytelling oriented in her approach.

It

also led to some tension in the editing room. Cutting the picture

together in the attic of their home, the long work hours and

strenuous circumstances of its making sometimes brought out

unpleasantries.

"I like to become emotionally involved in a movie," she says.

"I want to be scared, I want to cry, and I never cared for

THX because it left me cold. When the studio didn't like

the film, I wasn't surprised. But George just said to me, I was

stupid and knew nothing. Because I was just a Valley Girl. He was

the intellectual." [xxxv]

Still,

the two had a relatively healthy and happy relationship. Dale

Pollock writes that they were "the picture of domesticity," with a

cute little hilltop house with a white fence. George's parents

remember a visit from their son and daughter-in-law during which

George playfully ordered Marcia around. "Wife, do this, do that,"

George's mother remembers. "He was just playing, but they had a

wonderful relationship." [xxxvi]

But

Marcia needed more than just domestic bliss--and she needed work

that wasn't something made by her husband. To make matters worse,

THX had bombed, Zoetrope basically folded, and the future

was looking bleak for them--she would take any job she could get. As

the ruins of Zoetrope settled from the company's collapse, George

was often on the phone in the Zoetrope office, trying to hustle

editing gigs for Marcia and get himself another directing job. Mona

Skager, an associate and assistant at Zoetrope, opened the phone

bill one day and was furious--"You've run up a $1,800 bill with all

these calls and none of them are about Zoetrope business." George

felt humiliated and had to ask his father for money, a difficult act

for a conservative man like George Sr., who felt his son was wasting

his time in the industry in the first place. Marcia came in and gave

Skager the check. Looking back, Coppola says that he would never had

done that to George and didn't realise Skager had confronted him

about it; "I always believed that incident was one of the things

that pissed George off and caused a breach." [xxxvii] In spite of

the slim work available in the area, George and Marcia decided to

stick with San Francisco, hoping they would be able to make

it.

Coppola

meanwhile was making The Godfather to get himself out of

debt and gave the Lucases jobs whenever he could--Marcia could edit,

so he had her cut together the many lengthy screentests, and George

could use the animation camera so he had him film the newspaper

montages. Fortunately,

opportunity soon came knocking--Bay-area filmmaker Michael Ritchie,

whom George knew through Zoetrope's connections, was making a film

starring Robert Redford called The Candidate and wanted to

hire Marcia as assistant editor. Not only was it a job on a decent

film, but the income came at a time when they were nearly broke, and

for the next few months she would be the sole supporter of their

household.

Making

Graffiti

George

had been searching for another project to put food on the table, but

he wanted it to be on his own terms--he turned down a $150,000

salary to direct a movie called Lady Ice, even as he and

Marcia struggled to get by. Seeking a more commercial vehicle, if

only to get them out of debt, Lucas decided to do a

coming-of-age story about young teens in Modesto with a rock and

roll soundtrack. Lots of his friends thought the idea was silly, but

Marcia was one of the few who had full faith in Lucas, and

encouraged him to do a more emotional, character-oriented

piece. She says:

"After

THX went down the toilet, I never said, 'I told you so,'

but I reminded George that I warned him it hadn't involved the

audience emotionally...He always said, 'Emotionally involving

the audience is easy. Anybody can do it blindfolded, get

a little kitten and have some guy wring its neck.' All he

wanted to do was abstract filmmaking, tone poems, collections of

images. So finally, George said to me, 'I'm gonna show you how easy

it is. I'll make a film that emotionally involves the audience."

[xxxviii]

George

was borrowing money from his parents, relatives and friends to stay

afloat, but eventually Universal signed on.

American

Graffiti was shot in less time and with less money than Lucas'

first picture, and the gruelling shoot made him sick and caused him

innumerable stresses, so much that he felt that he no longer wanted

to direct; no doubt, his inability to communicate did not make this

any easier. The film told a simple human drama which relied on

editing to interweave four stories in the narrative. Getting her

first crack as a feature editor, Marcia stepped up to the

plate--working alongside Verna Fields. It was, in fact, Universal

executive Ned Tanen who insisted Fields be on the picture, since he

feared that George was just using Marcia as an excuse to cut it

himself, but both Lucases probably didn't mind since they had

already worked with her when they first met, and George hoped she

would be a good buffer between himself and the studio. Minor

controversy surrounds Verna Fields' role on the film--given her high

status as one of the great editors of her time everyone assumed she

was the genius behind the film's masterful editing; Marcia, many

dismissed, was only on the film because of her husband. Yet Fields

only was onboard for half of the film's editorial lifespan; Fields'

next big editing gig, for Jaws, has a similar situation, in

which she admits she gets too much credit.

The

two of them--plus, of course, George--cut the film in the spare room

over Francis Coppola's garage, for he had just bought a house in

Mill Valley at George's urging; he was off writing The

Conversation in an adjacent house (one of the refugee projects

from the Zoetrope fiasco). There were frequent boccie bowling games

on the lawn, picnics, and sunbathing. It was the closest they ever

got to the original dream of Zoetrope, envisioned as having

such a casual atmosphere.

Lucas

looked at Graffiti footage every day and explained what he

wanted from Marcia and Fields--the only time he ever spoke to his

wife during the hectic post-production schedule. Walter Murch came

onboard as sound editor, and they together collaborated on the

difficult task of cutting the music to fit the scene. Marcia argued

George out of his original approach to the structure of the film,

which depended on a more rigid construction of cross-cutting the

different narratives, and she also was crucial in giving scenes

longer time to breathe, as Lucas then insisted on cross-cutting much

more frequently (as seen in Attack of the Clones--Marcia's

criticism was that the scenes either never developed or they lost

their dramatic momentum by aborting so

quickly).

Verna

Fields left once the rough cut had been assembled, since she had

another job lined up, but the film was almost an hour too long,

so for the next six months Marcia cut the film down along with Lucas

and Murch. For the next cut, Marcia listened attentively to George

and made the film the way he instructed. It was a disaster. Because

of the interlocking narrative structures, the film could not simply

be trimmed up in a conventional sense because removing one scene, or

part of a scene, affected the next narrative thread and threw off

the rhythm of the film. Lucas remarks: "You literally can have a

film that works fine at one point, and in one week you can cut it to

a point where it absolutely does not work at all." [xxxix] Now it

was Marcia's turn at bat--she took over and re-cut the film on her

own this time, while George worked with Walter Murch on the sound

design.

By

January 1973, Marcia had assembled the film for a test screening.

The release would be controversial--the test audiences absolutely

loved the film, yet the studio executives thought it was terrible.

Lucas was heartbroken as Ned Tanen called the film

"unreleasable," but Coppola defended Lucas at the screening,

offerring to buy the film from Tanen and whipping out his chequebook

to make the deal on the spot (after Tanen slinked away, he and

Coppola didn't speak for another twenty years). George was

devastated by the studio's negative reaction. Marcia believed in

American Graffiti and was irritated by her husband's

inability to fight for his movie, but he didn't seem to share in her

confidence. At the same time, Marcia realised the reality of the

situation: "George was just a nobody who had directed one little

arty-farty movie that hadn't done any business. He didn't have the

power to make people listen to him." [xl]

Eventually,

the film was released, though the studio trimmed off a couple

minutes of footage. It nonetheless won rave reviews--while most of

the post-Easy Rider films of the "New Hollywood" wave of

filmmaking had done relatively unremarkable box-office, American

Graffiti was a powerhouse hit that was an absolute

audience-pleaser. It grossed over $100 million dollars, and when

calculated in terms of budget-to-gross may be the most profitable

film ever made (Blair Witch Project cost less to produce,

but Graffiti only had a marketing budget of $500,000). It

also turned George and Marcia into overnight millionaires. After

years of struggle, years of living on the edge of poverty, they

finally made it big. They bought a large Victorian house in San

Anselmo--a bit of a fixer-upper, but a beautiful find nonetheless.

Marcia named it Parkhouse (it was on a street called Park Way) and

it would become the business centre of Lucasfilm until Skywalker

Ranch in the 1980s. One of Lucas' best films, Graffiti's

entire existence might not have been were it not for Marcia's

influence of expanding his tastes--"I made it for you," he

once told her. [xli] Later, in 1974, the film was nominated at

the Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay--and

Best Editing. Marcia desperately wanted to win, but the picture

failed to nab any of the above. George didn't really care; producer

Gary Kurtz was disappointed; Marcia cried. It would be another four

years before she would get her dream.

From Scorsese to

Star Wars

Even

before Marcia Lucas was an Oscar-nominated editor, her career was

taking off--Michael Ritchie was impressed with the young woman when

she had worked on his The Candidate, and recommended her to

his friend Martin Scorsese, who was looking for someone to edit his

feminist road movie Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore. "We

knew her, we liked her, and she was in the union," associate

producer Sandy Weintraub recalls [xlii] ; Scorsese was looking to

crew the picture with women in the hopes of making the film more

emotionally honest. Once again, George's connections had given

Marcia a crucial stepping stone. It also was an important point of

departure in her career--she had worked on things not made by George

before, but this was a really important film and she would be the

editor, not an assistant editor. Sandy goes on: "It was good for her

to get away from George and his house. Here she was, a wonderful

editor working on her husband's films. I don't think she got taken

seriously." [xliii] Marcia remembers the

time:

"Marty

called, and asked if I would do his first studio feature. He was

terrified of the studio executives, that Warners was going to give

him some old fuddy-duddy editor or a spy--the studios were

known for having spies on such projects. Marty liked to edit,

and I felt like I was being hired to cut a movie so I wouldn't

cut it, so I'd let the director cut it. But I thought, if I'm ever

going to get any real credit, I'm going to have to cut a

movie for somebody besides George. 'Cause if I'm cutting

for my husband, they're going to think, George lets his wife

play around in the cutting room. George agreed with that."

[xliv]

In

the end, Marcia won Scorsese's approval, and he let her cut the

picture herself.

Lucas

meanwhile made Parkhouse his office, and also rented out rooms to

his friends to use as offices, such as Hal Barwood and Matthew

Robbins. They would go down the street to cafes and share ideas and

check in on what each other was doing--Lucas was working on writing

his next project, The Star Wars. As production on Alice

Doesn't Live Here Anymore went on, Marcia had to go to Tucson,

Arizona, where the film was shooting, to begin cutting the

footage. George didn't like being separated from her and so he

packed his things and joined her, trying to hash out his first draft

screenplay. Alice's post-production was finished in

Hollywood once production wrapped, again separating the two

Lucases.

As

far as evidence suggests, Marcia stayed out of Lucas' way when he

first started writing the space epic. He made two attempts at a

treatment in early 1973, but the success of Graffiti kept

him from completing the first draft until the spring of 1974. Marcia

was busy with her own career at the time, cutting for Scorsese and

dealing with their newfound success like George was. Like many of

Lucas' friends, she didn't quite know what to make of the first

draft of Star Wars when Lucas showed it to her; she wasn't

a fan of the action serials like Lucas was, and found a lot of it

too bizarre, and without strong characters or dialogue. Lucas

listened to her and his friends' criticisms, but it would be another

year before he finally finished the crucial second and third

drafts.

After

that time, Marcia landed another high-profile gig. Martin Scorsese

had really liked the work she had done on

Oscar-winning Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and

wanted to have her edit his next film as well, the dark character

study Taxi Driver. Marcia was excited to be part of

Scorsese's circle, to be part of what were considered some of the

most significant American films being made. Marcia's respect for

Scorsese and non-plussed disposition towards Star Wars

seems to have rubbed George the wrong way--he would often

tell how his friends thought he should do an "important film"

like Taxi Driver but instead he wanted to make an action

B-movie for kids, to their puzzlement. Taxi Driver was

also cut by Tom Rolf and Melvin Shapiro, but it was Marcia who

was the supervising editor on the project, a task probably made

more challenging by Scorsese's heavy drug addiction at the time.

Marcia was set to cut the film on her own, and had seen the dailies

as Scorsese was shooting, but after a break in production there

wasn't enough time, and so Rolf, and later Shaprio, was added to the

roster; Rolf describes the three trading off scenes in a "homogenous

cutting process," a situation to be repeated on her next

film. [xlv] Taxi Driver, to everyone's

astoundment, became a commercial hit when it was released in 1976,

and it is today considered one of the greatest American films ever

made. Marcia received a BAFTA nomination for her editing work on the

film, and was later featured, at Steven Speilberg's

recommendation, in an ad by Kodak hailing women in the

film industry. John

Milius remembers:

"She was a stunning editor...Maybe the best

editor I've ever known, in many ways. She'd come in and look at the

films we'd made--like The Wind and the Lion, for

instance--and she'd say, 'Take this scene and move it over here,'

and it worked. And it did what I wanted the film to do, and I would

have never thought of it. And she did that to everybody's films: to

George's, to Steven [Spielberg]'s, to mine, and Scorsese in

particular." [xlvi]

Marcia's

rising career did not come without its troubles. For one, she had to

work in L.A., where Scorsese cut his movies. "What Marcia was doing

was very difficult," says George's close friend Willard Huyck.

"George wasn't going berserk or anything, but he wasn't happy about

the situation." [xlvii] The Lucas family tradition had never allowed

a woman to have an independent career--Gloria Katz notes, "That was

actually a very big step for George; it was consciousness raising."

[xlviii] George hated cooking and cleaning, and hired a

housekeeper while Marcia was away. Meanwhile, The Star Wars

still had not been green-lit, even if Fox had agreed to develop it,

frustrating him further.

Lucas

had re-configured much of The Star Wars for his second

draft, completed in January of 1975. He had finally come up with the

basic backbone of the film--the heroic journey of farmboy Luke

Starkiller--but his characterisation and dialogue were arguably even

worse than his first draft. Lucas, however, acknowledged that he was

a poor writer, and sought the guidance of others. "I'm not a good writer," he says in 1974. "It's very,

very hard for me. I don't feel I have a natural talent for it...When

I sit down I bleed on the page, and it's just

awful." [xlix] He had attempted to hire writers for

every one of his previous films, but experience taught him a

different technique--he would listen to the suggestions others had,

but write the words himself. Marcia, along with many of

George's friends, critiqued which characters worked, which ones

didn't, which scenes were good, and Lucas composed the script in

this way. Marcia was always critical of Star Wars, but she

was one of the few people Lucas listened to carefully, knowing she

had a skill for carving out strong characters. Often, she was a

voice of reason, giving him the bad news he secretly suspected--"I'm

real hard," she says, "but I only tell him what he already knows."

[l] Pollock notes, "Marcia's faith never

waivered--she was at once George's most severe critic and most

ardent supporter. She wasn't afraid to say she didn't understand

something in Star Wars or to point out the sections that

bored her." [li] She kept her husband down to earth and

reminded him of the need to have an emotional through-line in the

film. Mark Hamill remembers: "She was really the warmth and heart of

those films, a good person he could talk to, bounce ideas off of."

[lii]

As

Hamill has also noted, she wasn't afraid to tell George if he was

headed in a questionable direction. Dale Pollock writes, "only

Marcia is brave enough to take Lucas on in a head-to-head dispute

and occasionally emerge victorious." [liii] Marcia explains: "I

don't think George is real close and intimate with anyone but me.

I've always felt that when you're married, you have to be wife,

mother, confidant, and lover, and that I've been all those things to

George. I'm the only person he talks to about certain things." [liv]

Walter

Murch comments further: "Marcia was very

opinionated, and had very good opinions about things, and would not

put up if she thought George was going in the wrong direction. There

were heated creative arguments between them--for the good." [lv]

When Lucas was having difficulty coming up with ideas or ways

of solving scenes and characters, he would talk about it with her;

she even helped come up with killing off the mentor figure of Ben

Kenobi when Lucas couldn't resolve the character in the last

quarter of the film. Lucas says:

"I was rewriting, I was struggling with that

plot problem when my wife suggested that I kill off Ben, which she

thought was a pretty outrageous idea, and I said, 'Well, that is an

interesting idea, and I had been thinking about it.' Her first idea

was to have Threepio get shot, and I said impossible because I

wanted to start and end the film with the robots, I wanted the film

to really be about the robots and have the theme be the framework

for the rest of the movie. But then the more I thought about Ben

getting killed the more I liked the idea." [lvi]

Often, Marcia reeled in Lucas' own sense of ego. She

encouraged him to do interviews as a way of raising his spirits, but

was also irritated by the auteur theory of critics

to credit every element of Lucas' films to himself; passing by

his office as she heard a journalist use the phrase "master

director," she snorted. "Doesn't he like that description?" the

journalist asked. "Oh, he loves it." [lvii] Mark Hamill also notes

in 2005 how her sensibilities influenced the content and structure

of his films:

"You can see a huge difference in the films that he does

now and the films that he did when he was married. I know for a fact

that Marcia Lucas was responsible for convincing him to keep that

little 'kiss for luck' before Carrie [Fisher] and I swing across the

chasm in the first film: 'Oh, I don't like it, people laugh in the

previews,' and she said, 'George, they're laughing because it's so

sweet and unexpected'-- and her influence was such that if she

wanted to keep it, it was in. When the little mouse robot comes up

when Harrison and I are delivering Chewbacca to the prison and he

roars at it and it screams, sort of, and runs away, George wanted to

cut that and Marcia insisted that he keep it."

[lviii]

One

interesting bit of trivia relating to her and Lucas' cinema is that

Indiana, the Alaskan malamute that gave Indiana Jones his name and

also gave Lucas the inspiration for Chewbacca, was in fact Marcia's

dog, not George's. [lix] On the subject of Indiana Jones, Dale

Pollock provides an anecdote which demonstrates how Marcia's

presence in her husband's life influenced his films in subtle but

significant ways--in this case, changing the ending for Raiders

of the Lost Ark:

"[Marcia] was instrumental in changing the ending of

Raiders, in which Indiana delivers the ark to Washington.

Marion is nowhere to be seen, presumably stranded on an island with

a submarine and a lot of melted Nazis. Marcia watched the rough cut

in silence and then levelled the boom. She said there was no

emotional resolution to the ending, because the girl disappears.

'Everyone was feeling really good until she said that,' Dunham

recalls. 'It was one of those, "Oh no we lost sight of that." '

Spielberg reshot the scene in downtown San Francisco, having Marion

wait for Indiana on the steps on the government building. Marcia,

once again, had come to the rescue."

[lx]

Star

Wars had a hectic shoot in 1976. This wasn't anything like the

low-budget pictures George had made before--this was a big,

expensive epic, shot in north Africa and on giant U.K. soundstages.

George was often miserable and homesick, and his inability to

connect to strangers left the foreign crews hostile to him. Marcia

went with him to Tunisia, but the months in England during

pre-production were lonesome; he wrote Marcia letters all the time,

and kept a picture of her taped to the inside of his briefcase.

Eventually Marcia moved there, renting a cottage for them in

Hampstead; while they were away in Tunisia, burglers broke in and

stole his video equipment.

When

Lucas returned home, he was exhausted and disappointed in his film;

Marcia had to rush him to the Marin General Hospital because of

stress-induced chest pains not long after they got back. Lucas

had hired a U.K. union editor--John Jympson--to cut the film while

they were in England, but when Lucas had seen the rough cut he was

horrified; the film was dull and without any of the kinetic energy

he had envisioned. Jympson was fired, and Marcia took his place,

starting over from scratch with George once they were back in

California, working in the Parkhouse carriage house which was

converted into an editing building. "He asked Marcia to work on

the final battle sequence, so ILM could start, but he needed someone

else to start at the beginning," says Richard Chew, [lxi]

whom Lucas knew from Coppola's The Conversation and

John Korty's films, and was hired not long after Marcia began

cutting. With the entire Jympson cut junked wholesale, the film

needed to be re-ordered back into dailies so that Marcia and Chew

could totally start over, a laborious task for the editors,

assistants and film librarians. "No one had been editing on the

movie for several months," Lucas states in The Making of Star

Wars, "so the first thing we had to do when we got back to San

Anselmo was to reconstitute everything that had been cut in England,

put it back in dailies form, and start from scratch. It turned out

to be even more of a tremendous job than we thought it was going to

be. We were running against a terrible time problem, so we hired

[another] editor, Richard Chew. He and my wife Marcia, who was also

an editor, raced to get a first rough cut of the movie ready by

Thanksgiving." [lxii]

The

workload was daunting. Carol Ballard walked in Parkhouse one

day at 6AM to find a bleary-eyed Marcia still cutting. Lucas was

cutting the Falcon gun-port battle himself, Chew states, "then

he went upstairs to his editing room and his Steenbeck editing table

and looked through all the trims, while I continued working from the

beginning of the film and Marcia was working on the

end." [lxiii] A third editor, Paul Hirsch, whom Lucas knew from

De Palma's Carrie, was later hired since there was so much

to do. "Marcia Lucas called me," Hirsch recalls. "And she said,

'Things are going a lot slower than we had hoped; our editor in

England didn't work out and we're having to recut everything. We've

got Richard Chew on the picture--but we're not getting enough

done!'" [lxiv] He accepted the offer but admits being nervous. "I

was a little intimidated," he says, "because both Marcia and

Richard had been nominated for Academy Awards before, and I was

just this kid from New York, but they were great." [lxv] He was

stationed on the Moviola, but it did not agree with him. "I had

forgotten how many years it had been since I had worked on one, so I

was all thumbs, breaking the film, dropping it, and wasting a lot of

time just trying to get the film to go through the machine. So

Marcia said, 'I don't care, I'll work on the Moviola.' After that, I

was working upstairs in George's room on the Steenbeck."

[lxvi] Marcia and Chew remained downstairs, closer to the

assistant editors and coding machine (used for syncing ILM shots).

Marcia

continued to work on the film as the months went by, trying to

fashion a more emotional experience from what she had to work

with.

The

Death Star trench run was originally scripted entirely different,

with Luke having two runs at the exhaust port; Marcia had re-ordered

the shots almost from the ground up, trying to build tension lacking

in the original scripted sequence, which was why this one was the

most complicated (Deleted Magic has a faithful reproduction

of the original assembly, which is surprisingly

unsatisfying). She warned George, "If the audience doesn't

cheer when Han Solo comes in at the last second in the Millennium

Falcon to help Luke when he's being chased by Darth Vader,

the picture doesn't work." [lxvii]

One

curiosity of note is that she was one of the few people

who was in favor of the Jabba the Hutt scene (before the Greedo

dialogue was re-written), and initially argued in favour

of keeping it in the film. She describes:

"Jabba was a big debatable item. George had never liked

the scene Jabba was in because he felt that the casting was never

strong enough. There was an element, however, that I liked a lot

because of the way George had filmed it. Jabba was seen in a long

shot and he was yelling, while in the foreground, in a big close-up,

Han's body wiped into the left corner of the frame and his hand was

on a gun and he said, 'I've been waiting for you, Jabba.' Then we

cut to Han's face and Jabba turned around. I thought it was a very

verile moment for Han's character; it made him a real macho guy, and

Harrison's performance was very good. I lobbied to keep the scene.

But Jabba was not terrific, and Jabba's men, who all looked like

Greedo, were made of molded green plastic. George thought they

looked pretty phony, so he had two reasons for wanting to cut the

scene: the appearance of Jabba's men and the pacing of the movie.

You have to pick up the pacing in an action movie like Star

Wars , so ultimately, the scene wasn't

necessary."

[lxviii]

2007's The Making of Star Wars treats Chew as the

primary cutter and only credits the space battle and the (deleted!)

Anchorhead scenes to Marcia as a solo editor, but given the book's

tendancy to downplay her (not even including her photo on the

editors page) and the fact that she was not spoken to for the book,

this is suspect (other publications, like Baxter and Pollock, treat

her as the main cutter). By October or November 1976, the editing

team had prepared a new rough cut; in the final crunch, the three

editors began to trade off scenes as a trio. "We put it all together

and spent about three or four days as a tag team," Hirsch says.

"George, Richard, Marcia and I would sit at the machine each for a

couple of hours, taking turns and making suggestions. The last day,

we did this for about twelve hours." [lxix] Alan Ladd Jr. flew in

for the screening, and walked out elated--he was convinced the film

would be a hit.

As

Marcia continued to re-work sequences as late as December of 1976,

Martin Scorsese called her up--his editor of New York, New

York had died, and he needed her to finish the film. Marcia

was, frankly, sick of working on Star Wars, and was looking

forward to something not made by George and something she

considered more artistic. George had another two editors onboard and

the film was on its way to being finished. Even still, he was not

pleased. "For George the whole thing was that

Marcia was going off to this den of iniquity," Willard Huyck

explains. "Marty was wild and he took a lot of drugs and he stayed

up all night, had lots of girlfriends. George was a family homebody.

He couldn't believe the stories that Marcia told him. George would

fume because Marcia was running with these people. She loved being

with Marty." [lxx] Things at Lucasfilm weren't as unremarkable as

they seemed; Marcia would later confide in Lucasfilm marketing

genius Charles Lippincott that if she ever had to work with her

husband on a film again, "it would be the end of their marriage."

[lxxi]

In late spring of 1977, Star Wars was

screened for studio executives and many of Lucas' friends. When

the house lights came up there was no applause in the silent

room, and Marcia, who was always apprehensive about the

film, was in tears. "It's the At Long Last Love of

science fiction," she cried. "It's awful!" Gloria Katz took

her aside. "Shhh! Laddie's watching," she hushed. "Marcia, just look

cheery." [lxxii] Marcia tried to raise George's spirits and

give him some feedback, but when the Lucases and a bunch of friends

went out to dinner to discuss the film, Brian De Palma mocked and

joked about how cheesy it all was; Marcia was terribly upset with

him for kicking George while he was down. She later called him up

and asked him to talk to George, cheer him up; "he respects you,"

she said. De Palma eventually ended up re-writing the opening crawl

with Jay Cocks.

Paul Hirsch and Richard Chew finished the edit after Marcia left

but she stopped by and helped her husband out when she could as

George raced to the finishing line. Marcia, meanwhile, was busy

finishing up New York, New York. Marcia and Scorsese

invited Lucas to take a look at the movie in the editing room, and

he recommended that if the lovers had a happy ending the film would

make millions more; such an ending would not have fit the characters

or film and Scorsese became depressed, knowing he could never make a

movie for the masses. By May, the picture cutting on New York,

New York was done, but Marcia was also supervising the film's

sound editing at MGM studios--the same place George was mixing sound

on Star Wars. Their two jobs overlapped at a critical point

that both had been too busy to even realise: Star Wars had

opened. Lucas recalls:

"I was mixing sound on foreign versions of the

film the day it opened here. I had been working so hard that,

truthfully, I forgot the film was being released that day. My wife

was mixing New York, New York at night at the same place we

were mixing during the day, so at 6:00 she came in for the night

shift just as I was leaving on the day shift. So we ran off across

the street from the Chinese Theatre--and there was a huge line

around the block. I said, 'What's that?' I had forgotten completely,

and I really couldn't believe it. But I had planned a vacation as

soon as I finished, and I'm glad I did because I really didn't want

to be around for all the craziness that happened after that."

[lxxiii]

The vacation was

in Hawaii, their first one in years, and they desperately deserved

it. Steven Spielberg and his wife soon joined them, bringing news of

the growing Star Wars mania, and Alan Ladd Jr., president

of Fox, excitedly phoned up Lucas every night to report the

staggering box office grosses. George and Marcia were stunned.

George wondered how he would spend all the millions of dollars that

would be coming their way, but all he could find was a frozen

yoghurt franchise on the resort, which he toyed with buying. He then

thought of restoring the Parkhouse office to its full

splendor--which probably led to his vision of Skywalker Ranch. For

Marcia, the success of Star Wars meant something else--they

could finally settle down. Graffiti had made them

millionaires, but George had funnelled much of it into his film, and

neither was sure if the success would last--Star Wars was

the darkhorse investment return. George was planning on retiring.

Marcia was planning on having a baby. Finally, it seemed like they

could have a real life.

The Beginning of

the End

Or so it

seemed. Marcia is quoted in a summer 1977 article in

People magazine as saying "Getting our private life

together and having a baby. That is the project for the rest of the

year." [lxxiv] After trying to get pregnant, the Lucases got

some bad news from the doctor: George was sterile. As Pollock notes,

the news was a bit difficult to accept at first, and must have

returned the strain to their relationship that just seemed to have

been lifted; Marcia and George would never be able to conceived a

child together. But if the thought of adoption seems obvious, it was

not something the two of them were ready to jump into just yet. And

George, despite claiming to be ready to retire, was about to embark

on his most ambitious project to date.

"The idea for [the Ranch] came out of filmschool," Lucas

explained at the time. "It was a great environment; a lot of people

exchanging ideas, watching movies, helping each other out. I

wondered why we couldn't have a professional environment like that."

[lxxv] With Star Wars becoming the most

successful film of all time by the year's close, Lucas saw what

opportunity he was now given. Here was his chance to institute the

dream that his mentor Coppola never had the resources to do. Lucas

decided to turn Star Wars into a franchise, intended to

support the costly facility. This also meant that Lucas had to use

much of his earnings from Star Wars to buy the real estate,

in Marin County--an action that no doubt must have worried Marcia.

Lucas hired Irvin Kershner to direct Empire Strikes Back,

thinking that the film would be relatively quick and easy to

make--which turned out to not be the case at all. Even as Lucas said

he was going to step back he saw himself becoming more and more

involved in the film--Marcia was supposed to take a vacation to

Mexico with him in 1978, along with their friends the Ritchie's, but

with screenwriter Leigh Brackett unexpectedly passing away Lucas

spent much of the trip in the hotel room writing. He also began

spearheading Raiders of the Lost Ark into production, which

he was writing and producing as well. Things weren't as simple as

they planned.

A peak of joy

finally appeared for Marcia amidst their increasingly hectic

lifestyle. On April 3rd, 1978, the 50th Academy Awards

ceremony was held, with Star Wars drawing a wealth of

nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best

Screenplay--and Best Editing as well. George was unsurprised that he

walked away empty-handed, but for Marcia there was a shock of

another kind. Star Wars won the Best Editing award, and she

and fellow co-editors Richard Chew and Paul Hirsch were all awarded

the golden statues. For Marcia, it was the culmination of a constant

uphill struggle since she entered Sandler Films in the 1960s and her

proudest professional moment. She was also one of the few women to

win an Oscar for the craft (only 5 others before her had, including

Verna Fields for Jaws two years

earlier).

Her husband,

meanwhile, was about to enter a world of hurt as Empire Strikes

Back began production in early 1979. Lucas wasn't interested in

making Star Wars films so he stayed home in California

while Kershner directed it in England. It was much more logistically

complicated than anyone had anticipated, and ended up weeks over

schedule and millions of dollars over budget. Lucas flew to England

a few times, but otherwise watched the picture disintegrate from a

distance, horrified as he saw his investment go to waste. He

re-edited the film out of desperation but it was a disaster, and

Kershner had to re-cut it (sometimes Marcia is thought to have

uncreditedly edited the film, though she probably just offered some

input). Tensions with producer Gary Kurtz became so great that the

two never worked together again. Lucas was soon diagnosed with an

ulcer and experienced the same anxiety-related symptoms that had

caused him to be hospitalised during the production of Star

Wars. Empire was not the fun romp he had envisioned in

1977, and his personal life was not any more

improved.

What was Marcia

doing during all of this? Apparently, not much. Scorsese had been

her number one employer over the previous half decade, but he was

between films at the time, New York, New York having done

bad business. But did she even want to work? Scorsese finally made

Raging Bull in 1980, but he went with Thelma Shoonmaker to

edit the picture, whom he hired as editor for virtually every single

film he has made since then. Lucas was able to coax Marcia into

sorting out the split-screen edits on More American

Graffiti, released in 1979, but she did so begrudgingly;

Eleanor Coppola asked her to edit her documentary Hearts of

Darkness, but she told her she was "too busy putting her house

in order." [lxxvi] Offers apparently continued to role in for her to

edit, and even to produce and direct. Marcia, however, seems to

have been waiting for George to settle down so that they could get

back to starting a family like he said he would do. "She worked so

hard for so many years without stopping that she just wanted to stay

home for a while," Eleanor Coppola remarked. [lxxvii]

Marcia busied herself by helping out on the business

end of Lucasfilm, and doing trivial things like organizing the

company softball and sailing teams. Empire later

opened to much success in 1980 and with its massive box office and

the flood of Star Wars merchandise produced in the

interggenum the Lucasfilm corporation had begun to rival Disney. But

instead of slowing down, Lucas went straight into production of

Raiders of the Lost Ark in 1980, and then began

construction of the massive Skywalker Ranch, an involved and

stressful undertaking which left him perpetually distant. "I don't

know how one person has that much energy," production co-ordinator

Miki Herman observed. [lxxviii]

The company meanwhile had expanded to include many smaller

divisions, such as Sprocket Works and the computer division, and

Skywalker Sound, requiring careful management and a ballooning

business team. In 1979, the company fourth of July picnic included

less than fifty employees, but by 1982, there were over a thousand

of them--friends and employees began referring to the sprawling

complex as "Lucasland." Producer Gary Kurtz looks back on this stage

in Lucas' life, when the Lucasfilm empire swallowed him up, and

muses:

"The saddest thing about watching that process

was the slow takeover by the bureaucracy...With that slowly came

this thing about dress code, company policy, and nobody talking to

press, and a firm of PR people, and it was quite frustrating really.

I was there longer than anybody, and had been with him for the

longest period of time, and I just felt that I didn't like it...The

bureaucracy grew and grew. You couldn't talk to George. You had to

talk to his assistant. It became more Howard Hughes, in a way. I

decided I was more interested in working on interesting films than

in being tied to a machine like that." [lxxix]

Skywalker Ranch was Lucas' biggest project yet, and Marcia

begrudgingly found herself a business person with her husband,

overseeing management on the facility. Sacrificing her career, she

tried to find some kind of creative outlet by involving herself in

the Ranch's design, hoping that her husband would soon diminish his

imperial reach. George's reciprocation, conveniently, was to

continue to work on his Ranch project, rationalising that she could

use the facility as well. "Marcia has sort of put her editorial

career on hold," Lucas said in 1981, "and is now working as an

interior designer. I don't really know if she'll go back to

editing--and she's a good editor. Usually the offers are to go to

New York or to go to Los Angeles, and that's no fun for us. It's

like six months apart, and coming home at weekends maybe. But once

we get our facility up here, if a director wants her to edit, it

will be much easier to convince him to do it up here rather than

wherever he lives. The whole reason for the ranch actually--it's

just a giant facility to allow my wife to cut film in Marin County."

[lxxx] As author John Baxter notes, however, the joke was probably

lost on Marcia, who stood by, befuddled why a man who was supposed

to be retiring was building a multi-million-dollar mini-studio at

the expense of his personal life.

Marcia saw the

same process occurring in Lucas' friend and mentor, Francis

Coppola, though Lucas agreed that Coppola's ego had become

unfathomable since Godfather, Godfather II and

Apocalypse Now turned him into the biggest director in

history, and she especially empathised with Eleanor, Francis' wife.

"It was no secret that Francis was a pussy hound," Marcia

remarks bluntly. "Ellie used to be around for half an hour or so,

and then she'd disappear, go upstairs with the kids, and Francis

would be feeling up some babe in the pool. I was hurt and

embarrassed for Ellie, and I thought Francis was pretty disgusting,

the way he treated his wife." [lxxxi] Following in the steps of

Lucas, Coppola too became distant with his grandiose ambitions and

attempted to build his own studio as well, alienating even

Lucas.

George, however,

had been mulling over things after the

Empire Strikes Back fiasco, as his life continued to be

consumed by work. When he began making the Star Wars sequel

in 1977, he thought it would be the first of eleven sequels that

would provide the funding for Skywalker Ranch to maintain its annual

million-dollar overhead. By 1979, he altered this number to eight

sequels. Yet after the film was done production, much had changed,

and the business drama of 1980, which included re-organizing

Lucasfilm and firing president Bob Greber, left him suffering

chronically from headaches and dizziness. He was quite literally

working himself to death, not having realised just what an

undertaking he was immersing himself in, and Marcia begged him to

step back while their relationship still had a chance of surviving;

as business partner in Lucasfilm, things were no fun for her either.

"He's doing a thousand things all the time," she said. [lxxxii]

George agreed--and they also began seriously thinking about adopting

a child, finally.

"I see [my family] a couple hours a night and maybe on

Sundays if I'm lucky," Lucas said at the time, "and I'm always real

tired and cranky and feeling like, 'Gee, I should be doing something

else.' I sort of speed through everything...It's been very hard on

Marcia, living with someone who constantly is in agony; uptight and

worried, off in never-never land." [lxxxiii] His contract

with Fox was for three Star Wars films and so that's what

he would make--his next Star Wars sequel would be his last.

It would also be his final ace-in-hole to pay off the Ranch, which

he vowed would be his final mega-project before settling down and

enjoying the fruits of his labour.

But life wasn't

all bad, of course; the Lucases struggled to remain normal, and

remain attached to each other. For George, this was most difficult

of all, constantly distracted by his workaholic mindset and often

leaving him physically absent, but Marcia's down-to-earth

sensibilities kept him grounded and offered a much-needed alternate

perspective for him, and she helped him grow as a person. Pollock

writes:

"Marcia admits it has been a struggle. She was never

pleased that George's hobby was also his work. She nags him to read

books for recreation, not research. Almost grudgingly, he now reads

contemporary novels by James Michener and James Clavell and classics

by Robert Louis Stevenson and O. Henry...Marcia also gets George to

play tennis with her, his sole form of exercise, as a small paunch

testifies. Marcia can still make George laugh--'She's a funny lady,'

Bill Neil says approvingly. 'She's loosened him up considerably.'

She also serves as the butt of her husband's dry, sardonic humor: at

the Raiders wrap party in Hawaii in 1980, George persuaded

producer Frank Marshall to tumble into Marcia's birthday cake and

was ecstatic when the stunt came off flawlessly. Marcia's off-color

remarks still make Lucas blush, but he's more affectionate now than

in the past--he'll even put his arm around her in public."

[lxxxiv]

Marcia said to Denise Worrell: "I've been after him for

years to get some other interests to help him relax. He's been

skiing twice now, and he's a little more interested in exercise.

From time to time we have parties if a friend is getting married, or

two to three times a year we have six or eight close friends over

for dinner and then go see a movie in the projection room."

[lxxxv]

In 1981, an

unusual lull in their lives, a child finally entered. Marcia and

George adopted a daughter, Amanda. Hoping to clear the table for

family life, Lucas hired Lawrence Kasdan to finish writing

Return of the Jedi , Richard Marquand was brought in to

direct, and producer Howard Kazanjian ensured a smooth

production--things seemed like maybe they would be better. Marcia

recalls with fondness this one brief glimpse of domestic

happiness:

"I make everyone leave at six o'clock so that