|

Home

FAQ

The Book

Articles

Links

Contact

|

|

The Influence and

Imagery of Akira Kurosawa

Part I:

Understanding Kurosawa and

Lucas

A constant thread found throughout

The Secret History of Star Wars is the undeniable influence of

one of the greatest directors to ever work in the art of motion pictures--Akira

Kurosawa. Lucas drew upon Kurosawa's style, characters,

visuals and content when writing all of his Star Wars pictures,

stewing them into a melting pot of sources that gives the films

their power. The specific characters and plot elements that Lucas

harvested for use in his Star Wars saga are mentioned throughout the

book, but now I wish to delve into this issue in further detail, and

especially address the visual components. In order

to understand Lucas, and

understand him as a visual storyteller, it is vital to first

understand Kurosawa.

Kurosawa had a fascinating childhood, recalled vividly in his autobiography--which

itself should be examined and dissected as another narrative

story in Kurosawa's repertoire--and, like Lucas, had a

strict upbringing that was later shed for liberalism and the arts.

Kurosawa himself was from a samurai family, and his father was

a strict disciplinarian with strong military ties--tradition was honored in

the Kurosawa family, and one could say that Kurosawa very

early developed an intimate reverence for the noble warrior class of

Japan's past. He was made to study calligraphy and martial arts at

an early age, and recalls many days trekking the miles and miles to

practice Kendo at 5:30 AM, stopping to pray in a Hachiman shrine along

the way as is tradition, before exhaustingly going to school afterwards

at 8. As he grew older, he emerged as a talented painter, and

hoped to pursue a career in this field. He also became increasingly

involved with Japan's tumultuous political scene. He championed

humanism and equality, and joined the socialist movement, actively

taking part in demonstrations and secret underground rebel groups

before police raids dissuaded him. This is essential insight into

the cinema of Kurosawa--his was a social cinema, one politically

motivated, much like Lucas' (although that is another discussion).

His earliest films are mostly absent of the medieval setting

and majestic pageantry of his famous samurai films--they were

contemporary dramas concerning the social ills of post-war Japan.

What is lost on many casual viewers, and especially Star Wars fans,

who mostly look at his later samurai epics as "mythic" storytelling

adventures, is that they were primarily something entirely

different--they were extensions of his earlier, contemporary-set

dramas. In searching for a way to comment on the state of modern

Japan, Kurosawa retreated into the past, using it as a mirror.

Ikiru feeds into Seven Samurai, High and

Low is a modern-set reflection of Throne of Blood, and

Yojimbo, for all its exaggerated action and melodrama, seen

mostly as a chambara

"swordplay" flick, really

is a comic exaggeration of Kurosawa's own

times.

Lucas himself set out to do this with his

earliest cinema. His student films usually had a strong social or

political message, not surprising given that he was strongly

involved with the liberal college scene of the mid-60's, and his

first feature, THX 1138, was a pessimistic--or, perhaps

realistic--reflection of the anxiety that gripped Watergate-era

America. It used the future to comment on the present. Lucas bounced

backwards with his next film, this time using the past, utilizing a

bygone era as a means of showing what the present generation had

lost. Lucas' cinema had undergone a fundamental change here,

however--the bleak cynicism that characterized THX was now

replaced with warm optimism. His next film, however, would take the

heroic character model that he had instigated in THX and

developed in Graffiti and now transpose it into the world

of pure fantasy. Star Wars

, as he would call it, was

meant to be a challenge to the gritty Watergate-era cinema of

New Hollywood, a story meant to inspire and move, to thrill and

excite.

Kurosawa too, had attempted this. Most of his

films were of a rather serious nature, and with a dark undercurrent

forebodingly coursing through them--but, once in a while, he would

make a conscious choice to craft a commercial tale, designed to

please audiences and make back some money so that he could continue

his other, more "art house"-oriented cinema. He had previously in

1945 made an adventure tale based off medieval Japanese plays and

legends, and, in 1958, when he was Japan's most powerful director,

finally had the professional muscle to remake it with the scope and

grandeur that he had initially wanted. The result was a frivolous,

fairy-tale-like adventure film that remains as one of Kurosawa's

most entertaining: The Hidden Fortress

.

Thus, it is no surprise that the two paths of

Lucas and Kurosawa inexorably crossed at this intersection. To

make his own commercial fairy-tale, Lucas set about remaking

Hidden Fortress, changing the landscape from post-medieval

Japan to one that was based in science-fiction. This is what his

1973 synopsis was. Following this, he altered and expanded it quite

considerably, resulting in the 1974 rough draft, and then made even

more drastic changes for the 1975 second draft, which laid the basic

groundwork for the final film, and which also contained influences

from other Kurosawa sources (a frequently cited one being the

cantina brawl, taken from Yojimbo

).

The scope and range of

Kurosawa's influence on Lucas is wide and varied. Elements crop up

in Lucas' films in regular pockets, the frequency and consistency of

which suggest that many of them are less to do with willfull copying

but more with subconscious absorption of the whole of Kurosawa's

work. Kurosawa is cited by Lucas as being one of his primary cinematic

influences, and part of Lucas' respect for Kurosawa, I

think, stems from the fact that Kurosawa himself was forged out

of the exact same influences that Lucas was. He was a traditionally-raised icon

for his country, with a strong interest

in painting and history, a passionate liberal who was interested

in social and political change, and one who was heavily oriented

in visuals, and especially silent cinema. In many ways, Kurosawa

sums up all of Lucas' defining characteristics and influences into

one neat package.

One may look at Kurosawa's themes and draw many

parallels: the master-student relationship, frequently expressed in

Kurosawa's early films through the powerful and brilliant

pairing of Takeshi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune, the dichotomy of

illusion and reality, the division of classes and the rise of the

peasant, government corruption, and the journey and awakening of a

hero. Like Lucas, Kurosawa was also a student of history, and he

went to meticulous lengths to research his "jidai geki" or period

epics--Seven Samurai's greatest contribution to the genre

of samurai-oriented films was its depiction of the class and

environment in realistic and historically correct terms, often

shattering myths and misconceptions held (ones which were undone and

re-popularised by the post-Yojimbo

onslaught of tired chambara

flicks).

But I want to focus now on a particular aspect

of Kurosawa and his connection to Lucas, and

that is his style and use of visuals. Lucas is not a

filmmaker whose strengths lay in writing or directing actors--his films work mainly because they

speak to us at a direct, and perhaps more primal,

level, which is visuals. Lucas is above all else a visual storyteller.

His sense of camera, of movement, of editing are what define his

cinema and what elevates it to greatness. And all of these

elements can be traced back to Kurosawa. Lucas' is a cinema of

action, and the same can be said of Kurosawa. It is in the visual

aspect that we must understand Kurosawa above all else if we are to

fully appreciate the films of George Lucas. As I mentioned before,

some of these aspects are not due to direct copying per se, but more

due to the fact that Kurosawa himself sources the same influences of

Lucas. We shall examine these elements first.

It has been said that Kurosawa, despite being

Japan's most revered and popular cinematic artist, is decidedly

"unjapanese." Many of his influences were western, and his films definitely reflect this. Standing in

stark contrast to "traditional" Japanese masters like Ozu and

Mizoguchi, Kurosawa's cinema is a much more visually dynamic one, his

frames filled with details and his lens frequently moving, his editing

quick and lively. Kurosawa was, perhaps more than anything, a product of

the silent age of cinema. Growing up in

the 1910's and 1920's, these were the first films

he was inundated with; every week, his mother would take

him to the local cinema, and the young Kurosawa quickly absorbed

the entire pivotal silent era. His father too frequently took

him to the movies where he saw mainly American and European

ones, such as those by Chaplin, and the imported American

action serials. His older brother, Heigo, the prototype mentor figure in his

films, worked in the silent cinema business in a sense, as

a "benshi": in Japan, "benshi" were a sort of storyteller,

actors who would narrate the silent cinema projection and embellish the life

of the images through running commentary. It was Heigo's love of silent cinema

that bequeathed unto Akira the same passion. "I think

he comes from a generation of filmmakers that were

still influenced by silent films, which is something that I've been

very interested in from having come from film school," Lucas

notes. Kurosawa was likely influenced by the subsequent development of

German expressionism, and his films often attain the same cinematic

beauty and visually-driven emotion that masters such as F.W. Murnau

achieved in films such as Sunrise. Kurosawa's breakthrough

work, 1950's Rashomon

, is constructed as if a silent movie--the

opening sequence runs for nearly ten minutes, bereft of any

dialog, and the spoken word is only used to convey expository information;

the film looks and feels as if it were the born from the

fusion of Murnau and John Ford. Ford, perhaps greater in influence than

silent cinema, is evident in most of Kurosawa's work as well.

One of the reasons Kurosawa has been deemed to be westernized is

its similarities to the cinema of John Ford and Hollywood's golden era. He

idolized John Ford and studied the American western genre.

His use of camera, with its long tracking shots, efficient construction,

widescreen composition, and dynamic movement, recalls the

style of directors such as Ford and Hitchcock. Although

much of it is assuredly direct influence, Ford and Hitchcock

also share the same prime influence as Kurosawa--silent cinema,

for both of the above-mentioned western directors

began their careers in that medium.

Kurosawa also, very much like Lucas, was

interested in abstract visuals. It took him a long period of

exploration to reach this point, with his earlier films displaying

an emphasis on wide-angle photography with the camera placed close

to actors, in order to bring out the emotion in the most subjective

and direct ways. However, a curious crossroads passed in his content

and storytelling--just as his films began to drift away from

subjective emotional identification and into a colder,

intellectualized distance, he found a way to visually convey this.

Seven Samurai

is the transitionary film of Kurosawa's career--it is constructed

in the vein of his earlier cinema, being more straightforward in

its story and presenting strong, good-natured characters that

the audience is urged to identify with. For this reason it is often

the favourite of the many samurai pictures that Kurosawa made, for

his others would lack this perspective. The audacious production of

the film, however, necessitated a certain practical camera

technique. Because the action was immense in scale and involved many

actors, stuntmen, animals, extras and special effects, the set-ups were

not easily repeatable. Thus, the traditional method of filming

a scene--of using only one camera and filming an action again

and again from different angles--could not be practically adhered

to. Instead, Kurosawa was forced to use the multiple camera

technique. This allowed him to film a complicated action sequence in one or

two takes, since the cameras would be positioned to capture all

the shots at once. In the most complicated sequences, for example

the final rain-soaked battle, Kurosawa used up to five cameras

shooting simultaneously. To accommodate this, however, one is forced

into certain lens and camera placement options: because it would be

seen by the other cameras capturing the wide shot, for example, the

cameras which captured the close-ups and medium shots, instead of

using wide and medium length lenses and placed close or mid-range to

the action, were instead forced to be placed far, far away so as to

avoid being seen, and the action was then captured using telephoto

long-lenses. The effect of this was unplanned, but it would

change--and define--Kurosawa's visual style.

When one is shooting

with a wide angle lens, the distance between objects is exaggerated,

and a more three-dimensional space is captured--objects close to the

lens really do appear close, and they curve away and taper off into

the horizon, where distant objects truely do appear

distant.

(wide-angle shots from

Seven Samurai and Ikiru)

Long lenses, or telephoto lenses, have an opposite effect: they compress

space. They create an image that is flat and two dimensional.

Objects that are distant do not look as if they are very far

away from objects in the midground, and perspective and planes of

geography are skewered. Space relations can be maintained however, since one's area of

focus--or depth of field--is highly compressed and shallow as well: objects in the

background go into a complete blur and foreground objects

are fuzzy and indistinct, and hence the area in focus regains

its geographic perspective. In other words, the area that is

in focus is very narrow or shallow, and thus some semblance

of normal space relations are maintained. However, this can broken--if you

are shooting at high light levels, one is forced to

shoot at a smaller lens aperture, which destroys the shallow depth of

field. Thus, objects in the far distant are sharp and distinct, while

foreground objects do not become as blurred. When combined with

the compressing aspect of telephoto lenses, this effect is sometimes striking: the

planes of geography get skewered and objects in the background can

appear to be stacked on top of those closer, and space relations

disintegrate. Foreground and background are compressed together into

a single image where the space relations are rendered indistinct.

Because Seven Samurai

was mostly photographed outdoors in high light levels, the deep depth of

field was able to be maintained while

shooting with telephoto lenses, and the striking visual skewering noted

above was the result.

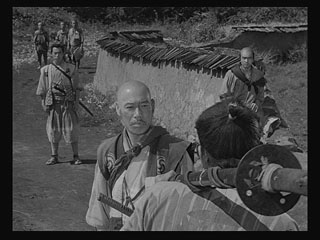

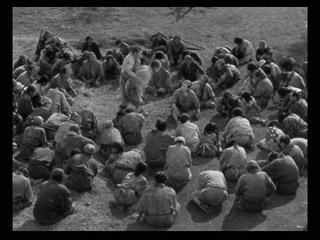

Here we see a shot of the villagers in

Seven Samurai

gathered in a group. This is a

normal looking shot, without much depth compression or perspective

skewering, and it lays out what the geography of the environment

actually is. However, when we cut to an intersecting shot using

telephoto lenses...

The

result is this. In the previous shot you can see the real

geography of the villagers--now, however, they are compressed together with a

long lens. They become visually stacked on top of one another

in a flat, two dimensional manner. Another, extremely fleeting example in the

film is the following shot:

Here we see the main appeal of the telephoto

lens: everything is rendered into flattened geometric patterns that take

on an abstract quality. The fenced wall closests to the audience

is quite a ways in front of the woman kneeling inside, and the

back wall, with its geometric slats, is even further away--but now

they loose their space relations and all become compressed together into

a two-dimensional image that has a geometric design quality.

Perspective is eliminated; even the ground between the woman and the

audience is rendered into a solid block that acts as another shape

in the aesthetic design of the shot.

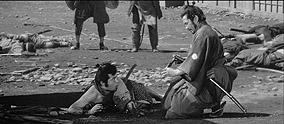

In this shot we see the result in an action

scene. The distances here are quite great: the villagers on

the right hand side are some distance away from the

two villagers by the hay-stacks on the left, and the

wooden barricade is some yards away from them in turn, while the

hillside behind that is a good half kilometer into the distance.

Now, however, they are all compressed into a single two-dimensional image.

Each object becomes stacked on top of one another in a bold

graphic, and perspective is skewered.

For Kurosawa, this was a marvellous discovery.

He had been hinting at trying to achieve this effect in his earlier

works--for example, in Ikiru he uses wide lenses but with

such a deep depth of field that background objects become just as

sharp as those in the foreground ("deep focus" it is known as, much

like Orson Wells put to iconic use in Citizen Kane).

However, with the use of long lenses in Seven Samurai, he

found an additional effect, which was the distortion of space. The

result was a total visual abstraction of image. From here on

Kurosawa would shoot almost exclusively with long lenses and

multi-camera set-ups. A by-product of this method was that

it often placed the audience at a distance, foregoing emotional

identification in favor of visual formalism. This was perfect for

Kurosawa because the content of his films was undergoing the same

transformation: the optimism and character-based subjectivity of his

earlier period was being replaced by dark pessimism and a detached

distance characterized through abstract visuals (for a good

parallel, Lucas' own THX 1138 utilizes these same

techniques, which we will soon see). This reached its peak with

1985's Ran

, a film utterly crushing with its bleak despair and

visually functioning in parallel: the shots are at their most telephoto

and distant in all of Kurosawa's career, and there is a complete

lack of close-ups. The film is photography at high angles, from

above and at a distance--- as Kurosawa put it "a Buddha in

tears," filmed from the perspective of divinity as it weeps at the

hopeless violence on Earth below.

(less extreme telephoto compression in Red

Beard and Yojimbo

)

(more exaggerated examples from Red

Beard

)

This is how Lucas himself forged his visual

design. THX 1138

is often misunderstood by many

as an attempt at emotional storytelling that ultimately fails--quite

the contrary, it actually is a piece of intellectual formalism

that succeeds so greatly that it often becomes emotional. It

is one told through design and through camera, and Lucas, like Kurosawa,

is attracted to a particular type of visual: one that is

interesting because it becomes abstracted. How fitting then that

Lucas, in contrast to most of his other films which use normal and

wide lenses, photographs the film in the exaggerated manner of

Kurosawa: with telephoto lenses and all the abstracted space

compressions that they bring (partially, this was also the fusion of

the other side of Lucas' visual influence--documentary technique).

For a cameraman--as this was Lucas' main profession and area of

influence at the time--the technique of Kurosawa was all-pervasive.

Lucas speaks in explicit terms of the photographic influence of

Kurosawa:

"It's really his

visual style to me that is so strong and unique, and again, a very,

very powerful element in how he tells his stories...he uses long

lenses, which i happen to like a lot. It isolates the characters

from backgrounds in a lot of cases. So you'll see a lot of stuff

where there's big wide shots, lots of depth, and then he'll come in

and isolate the characters from the background and you'll only focus

on the characters...you can't help but be influenced by his use of

camera."

It is in this way that THX 1138 is shot and told.

Almost without dialog, it is a film told in and

through visuals. Characters are scarcely developed;

dialog is at an absolute minimum; exposition is non-existant;

emotional subjectivity is mostly denied. It is a film of

intellectual formalism, expressed in visual design, specifically

through photography. This is where the power of the film stems from.

The camera is kept at a distance, and we are rarely encouraged to

identify with the protagonist on a truely emotional level--things

are kept formalized and abstracted. Lucas here uses close-ups more

frequently than in any of his other films, even his greatest

character successes of Graffiti and Star Wars , and the reason he often

frames characters so tightly is because they are rendered into

abstractions through the power

of the telephoto lens. Converse to Kurosawa, however, he

embraces the shallow depth of field that long lenses bring,

and emphasizes the out-of-focus abstractions. Without much in the way of character

and narrative, Lucas instead builds his film around the visual

exploration of action, rendered into abstract visuals through the

power of the telephoto lens.

Here we

see the flattening effect of long lenses, rendering the image graphically

and accentuating the geometric design of the environment

(the last two stills show Lucas' use of telephoto

lens to create shallow depth-of-field and thus render abstractions; the lizard

shot has a depth-of-field, or area in focus, of approximately

one inch). In the very rare instances where Lucas does use

wide-angle photography, it is extreme wide-angle, fisheye in some

cases, so that the image maintains the graphic distortion and

abstract quality that his shallow-depth-of-field and telephoto photography brought; see

below:

With the story told exclusively in

visuals we thus also see the parallel to Kurosawa's

cinema: action. Perhaps stemming from the shared influence of silent

era--which truely was an action cinema, a cinema told exclusively by

visuals and thus actions--Kurosawa's and hence Lucas' cinema are

ones both defined by action; movement through the frame, quick

editing and abstracted visuals render the events in a dynamic

excitement.

It may be argued that THX 1138 is the

best and truest example of the cinema of George Lucas, uncorrupted,

uninfluenced by outside forces, undiluted and without regard for

audience. Lucas frequently speaks about how he is truely an esoteric

and experimental filmmaker at heart, but his films betray this

assertion--they are traditional character vehicles and Hollywood

blockbusters. Except THX 1138. In this film we witness pure

George Lucas, including brief flashes of the quirky humor that would

be put to great use in his later efforts (ie., the malfunctioning

police robot who bumps incessantly into a wall, symbolizing the

useless technology of the government). However, much like Kurosawa,

Lucas' cinema would undergo a drastic change. Annoyed by the

rejection and failure of THX 1138, Lucas instead turned his

attention to the opposite direction: he deliberately set out to make

a commercial film. With this was born American Graffiti, a

warm and funny character piece, one which left behind the abstract

formalism of THX (though not completely) and embraced

subjective identification. The film was a hit and it encouraged

Lucas to set his sights even further down this path: to make a film

that was even more commercial, even more traditional--to emulate the

studio pictures of Hollywood's golden era. With this, his visuals

changed accordingly--the telephoto lenses turned into medium and

wide-angle lenses, and he brought forth the more traditional

Ford-like method of photography. This was encouraged by the fact the

film was not being photographed by Lucas himself and documentary

cameramen (as THX and Graffiti were respectively),

but by an "old boy" from the studio era of Hollywood, Gil Tayler

(though it is true that Lucas chose him because he liked his

documentary-like technique in Hard Days Night

). Here, Lucas' technique underwent the opposite metamorphosis

from Kurosawa's, going from formalism and abstraction to traditional

and subjective.

CONTINUE TO PART

II

Star

Wars, the Star Wars logo, all names

and

pictures of Star Wars characters, vehicles and any

other Star Wars related items are registered trademarks and/or

copyrights of Lucasfilm Ltd., or their respective trademark and

copyright holders. All other images are copyrights of Toho studios.

They are used here for educational purposes under fair use. Web site and all contents

© Copyright Michael Kaminski 2007, All rights

reserved.

Free website templates

|

|